Questions that feature multiple bad actors often ask you to determine who is a conspirator and who is an accomplice. The #1 difference is that conspiracy is a crime, while accomplice liability is a method of holding someone liable for another’s crime. Let’s discuss each concept in turn.

CONSPIRACY

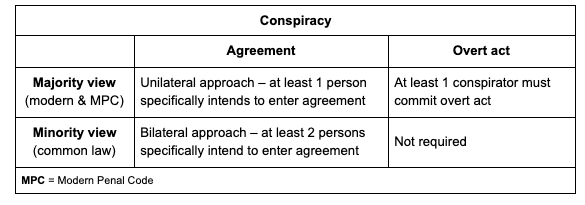

Conspiracy, at its core, is an agreement between two or more persons to commit a crime. Under the common law, conspiracy requires proof of at least two guilty minds. This requirement means that a defendant cannot be convicted of conspiracy if he/she intended to accomplish the crime but the other “conspirator” jokingly feigned agreement to do so.

In contrast, the prevailing modern trend requires only one guilty mind but also requires that at least one conspirator commit an overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy. Here’s a table to help you keep this straight:

Since conspiracy is a crime in and of itself, a conviction is appropriate once these elements are met—even if the target crime is not committed. If the target crime is completed, then the defendant can be convicted of both conspiracy and the completed crime.

ACCOMPLICE LIABILITY

Accomplice liability is a method of holding someone liable for another’s crime. It is imposed when a person:

- intentionally aids or encourages another (the principal) before or during the crime and

- does so with the specific intent that the crime be completed

This liability renders an accomplice liable to the same extent as the principal for the encouraged crime as well as any foreseeable crimes that occurred during the commission of the encouraged crime.

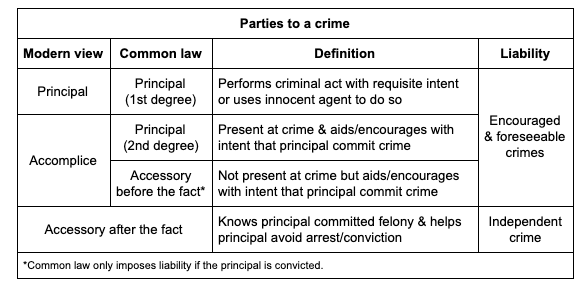

Keep in mind that the common law and modern trend use different terms to refer to a principal and accomplice. Here’s a table to sort it all out:

DO THESE CONCEPTS INTERSECT?

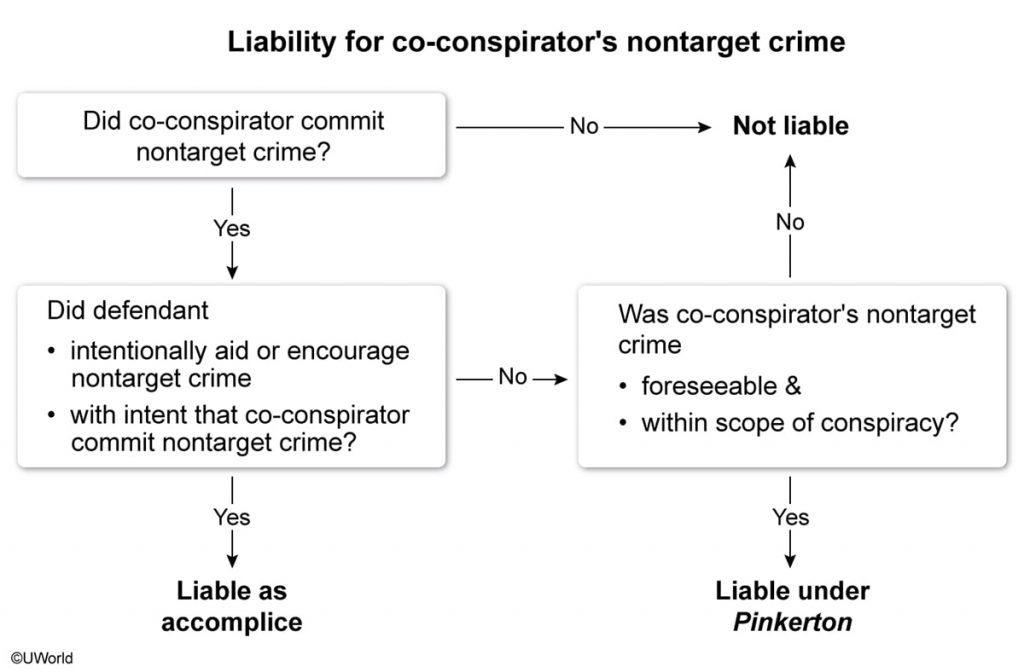

They certainly can! This intersection arises when a defendant entered a conspiracy to commit a crime and a co-conspirator committed a different, nontarget crime during the conspiracy. If the defendant intentionally aided or encouraged the co-conspirator to commit the nontarget crime, then the defendant is subject to accomplice liability for that crime.

But what if the defendant didn’t aid or encourage the co-conspirator in the commission of the nontarget crime? Under the Pinkerton Rule, the defendant is liable for any foreseeable crimes committed by a co-conspirator within the scope of the conspiracy.

Here’s a flowchart that helps bring these concepts together.

You can use this tip when answering practice questions in the UWorld MBE® QBank.