A consumer domiciled in State A sued a manufacturer and a retailer in a federal district court in State B for strict products liability. The complaint alleged that the manufacturer and the retailer are jointly and severally liable for $70,000 and $30,000 in damages, respectively, for harm caused by a defective kitchen appliance manufactured and sold by the defendants. The manufacturer and the retailer are both incorporated and headquartered in State B.

The retailer has asserted a $50,000 crossclaim against the manufacturer for breach of contract. The retailer claims that the manufacturer sent the retailer nonconforming power tools in its last shipment. The manufacturer has moved to dismiss the crossclaim for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction.

Should the manufacturer’s motion be granted?

A) No, because there is diversity of citizenship between the consumer and the manufacturer. [3%]

B) No, because there is supplemental jurisdiction over the crossclaim. [36%]

C) Yes, because the compulsory crossclaim failed to satisfy the amount-in-controversy requirement. [9%]

D) Yes, because the crossclaim is unrelated to the consumer's claims. [52%]

Note: The percentage next to the answer indicates what percent of UWorld users selected that answer option.

Explanation

Federal district courts have original subject-matter jurisdiction to hear disputes that arise from:

- federal-question jurisdiction – when the dispute arises under the U.S. Constitution, a treaty, or a federal law (not seen here) or

- diversity jurisdiction – when the opposing parties are citizens of different states and the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000.

To meet the amount-in-controversy requirement, a single plaintiff may only aggregate (ie, combine) claims against multiple defendants if the plaintiff alleges that they are jointly liable.

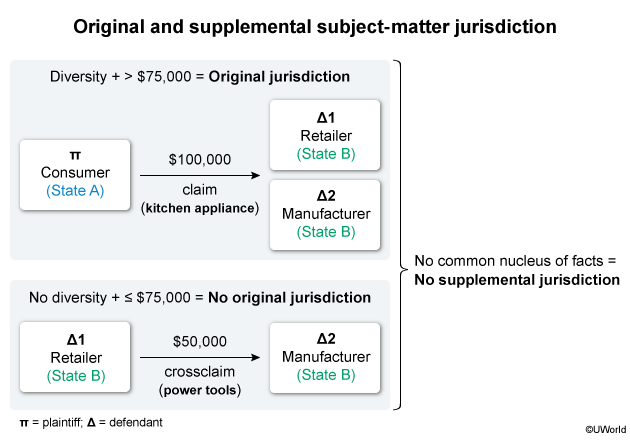

Here, the consumer (State A citizen) is diverse from the retailer and the manufacturer (State B citizens). And since the consumer seeks a total of $100,000 from the defendants ($70,000 + $30,000) under joint and several liability, diversity jurisdiction exists over the consumer’s strict products liability claims.* However, no diversity jurisdiction exists over the retailer’s crossclaim against the manufacturer since they are both State B citizens and only $50,000 is in controversy.

When a dispute involves multiple claims and one falls outside of the court’s original jurisdiction, the court may exercise supplemental jurisdiction over that claim. However, the court can only do so if the claims are so related that they share a common nucleus of operative facts. Here, the consumer’s claim concerning a kitchen appliance is unrelated to the retailer’s crossclaim concerning power tools. Therefore, the court lacks supplemental jurisdiction over the crossclaim and should grant the manufacturer’s motion to dismiss it (Choice B).

*The consumer’s strict products liability claim constitutes two claims because it is asserted against two separate entities. The defendants can only be held jointly liable for the total damages if the elements of strict products liability are established against both defendants.

(Choice A) Diverse citizenship between the consumer and the manufacturer does not change the lack of diversity between the retailer and the manufacturer or create supplemental jurisdiction over the retailer’s crossclaim against the manufacturer.

(Choice C) Crossclaims are permissive and can be asserted only if they arise from the same transaction or occurrence as another claim (not seen here). Had the retailer’s crossclaim done so, its amount in controversy would be irrelevant since supplemental jurisdiction would exist.

Educational objective:

A federal court may exercise supplemental jurisdiction over a claim outside of the court’s original subject-matter jurisdiction if it shares a common nucleus of operative facts with an original-jurisdiction claim.

References:

- 28 U.S.C. § 1367 (supplemental jurisdiction).

- United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715, 725 (1966) (establishing that a supplemental claim must derive from a common nucleus of operative facts as a claim within the court’s original subject-matter jurisdiction).