Contracts

If you've ever purchased or provided a goods or a service, chances are, you've participated in a contract. A contract is a legal document that protects all parties involved in a legally binding agreement. Although they are not a fun read (ever skip the fine print?), contracts are a vital part of conducting business, and you will see them often in your legal career.

With that said, the National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE®) has added contracts as a necessary component of the Multistate Bar Exam (MBE). Of the 175 scored multiple choice questions on the bar, you can anticipate about 25 of those questions to be on contracts.

Contracts Breakdown by Topic, Weightage and Tested Questions

In order to prepare for the contracts section of the bar exam, it's essential to know how it is organized, which topics are covered, and how they are weighted. The NCBE has based the majority of the questions on the common law, while the remaining 25% of the questions will focus on Articles 1 and 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC).

Thus, the first step when approaching any Contract question on the MBE is to determine whether to apply the common law or the UCC. As you will remember, the UCC is applied to the sale of goods, while all other contracts are governed by common law. Once you make this determination, it should be easier to identify which set of rules applies to each scenario.

Knowing which subtopics of Contracts will be tested on the MBE is also essential. The questions are divided into six categories, with some topics tested more heavily than others. For example, 50% of the questions will fall under either Formation of Contracts, or Performance, Breach, and Discharge, with each having 6-7 questions. The remaining 50% of the questions will deal with the other four categories: Defenses to Enforceability, Contract Content and Meaning, Remedies, and Third-party rights, each with only 3-4 questions. (See the chart below, which can be used as an MBE contracts outline.)

| Contracts Topics | % Tested | Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Formation of Contracts | 25% | 6-7 |

| Performance, breach, and discharge | 25% | 6-7 |

| Defenses to enforceability | 12.5% | 3-4 |

| Contract Content and meaning | 12.5% | 3-4 |

| Remedies | 12.5% | 3-4 |

| Third-party rights | 12.5% | 3-4 |

Formation of contracts

About 6-7 questions on the MBE will be on the formation of contracts. As stated previously, it's always a good idea to first determine whether the contract in the situation is governed by the common law or the UCC.

Remember that under common law, an acceptance must be the "mirror image" of the offer or it will be considered rejected. In contrast, the UCC follows the "battle of the forms" in which an acceptance containing different terms is still regarded as enforceable.

The next step is to determine exactly when a contract was formed. Often the NCBE will throw out a series of interactions between two parties, and it is up to you to order and classify them correctly (i.e., offer, acceptance, consideration) to determine whether there was mutual consent and, as a result, a valid contract.

Performance, breach, and discharge

Another 6-7 questions on the MBE will be on the Performance, Breach, and Discharge of contracts. As usual, first, you should determine whether the contract falls under the common law or the UCC to determine which rules to apply. For instance, under common law, you must decide whether there was a breach or the performance was substantial enough for the other party to be obligated to perform their duty. On the other hand, under the UCC, the seller has to provide a perfect tender of goods for one-shot deals, or the buyer can reject them (although the seller usually has time to correct the mistake). Other topics within this category include installment contracts, express conditions, warranties, impossibility/impracticability, and frustration of purpose.

Defenses to enforceability

Next, you will find 3-4 questions pertaining to defenses to enforceability on the MBE contracts exam. In some cases, such as when at least one party is a minor or incapacitated, there is a mutual misunderstanding or mistake, or there was deliberate fraud, it is easy to spot when a contract is not enforceable. However, other times, the scenario is less obvious, in which case you should consider whether it falls within the Statute of Frauds.

Note that the Statute of Frauds covers common law contracts for the sale of land, marriage, agreements involving goods worth over $500, and contracts lasting one year or more. Additionally, it covers UCC contract issues regarding the merchant exception and the maximum quantity of goods to be received. These instances require that the contract be in writing, contain the material terms, and be signed by the "party to be charged."

Contract content and meaning

There will also be 3-4 questions about contract content and meaning on the MBE. In these cases, you should decide whether the parol evidence rule applies to the scenario. For instance, if a party tries to add an additional term from the preliminary and/or oral negotiations to the final agreement, it is only allowed if there is partial integration of the contract, so watch out for that merger clause that says, "this is the full and final agreement"! Also, note that parol evidence does not apply to additions such as formation defenses, interpretations, condition precedents, clerical errors, or later modifications.

Remedies

Next, you can expect 3-4 questions dealing with contract remedies, but you most likely know them better as damages. Generally speaking, the non-breaching party will at least be entitled to expectation damages equal to the value of their position had there not been a breach.

Therefore, the general formula to calculate damages is as follows: the loss of value of the breaching party's performance + incidental costs + consequential costs – any expenses saved as a result of the breach.

It's essential to familiarize yourself with all the types of breaches and damages available to a party, such as reliance, restitution, rescission, specific performance, reformation, or remedial rights. Remember that when it comes to UCC contracts, which have various damage formulas, the key is ensuring that the non-breaching party ends up with the value they bargained for.

Third-party rights

Finally, there will be 3-4 questions regarding third-party rights on the Multistate Bar Exam. Generally, this means deciding whether a third party has the right to sue on a contract and against whom. Thus, the key is correctly identifying the type of situation (i.e., beneficiary, delegation, or assignment).

For example, a common assignment situation would be where person A owes money to person B, but person B assigns the right to receive the money to person C. In that situation, if person C does not receive the money, the question may ask whether/ who they can sue. Another common scenario is hiring a subcontractor whereby person A hires person B to perform a service, but then B delegates it to person C, who doesn't perform. In this case, it's important to remember that delegation is generally permissible even without consent, writing, or consideration when determining whether/who person A can sue.

How to Study for Contracts on the MBE

Now that you know what Contract Law topics are covered on the MBE, it's time to crack open the books! However, if you're still unsure how to study or where to start, don't worry - we've got you covered! Below are some tips on how to break down some common contracts bar exam questions.

Identify the Main Purpose

Again, we cannot reiterate it enough– the first step when approaching any contract question on the MBE is to ask yourself: "Does this scenario fall under the common law or the UCC?"

Unfortunately, this may not always be apparent, as with a catering contract that includes both goods and services being rendered. Instead, the best rule of thumb is to ask yourself: "What is the main purpose of the contract?" For example, if the caterer served people at an event, you would determine that the primary purpose is to render a service. In contrast, if the caterer were just going to deliver the food, it would primarily be a contract for goods.

Remember the Mailbox Rule

Let's say you send a rejection letter to an offer but then change your mind and send an acceptance letter. Do you have a contract or not? According to the Mailbox Rule, which governs the acceptance and rejection of transmittances by mail or email, that all depends. While this may sound confusing, this rule applies to contracts under common law and UCC- so listen!

The simple Mailbox Rule states that a contract is formed as soon as an acceptance is sent. In fact, even if you send a rejection after an acceptance is sent, and the rejection is received first, the contract is still considered formed (unless there was detrimental reliance). Conversely, a rejection takes effect only upon receipt. As a result, an exception occurs if you send a rejection first and then an acceptance. Then it depends on which response is received first by the offeror (opened/read or not). So, let's revisit the original question: If you send a rejection and then an acceptance, do you have a contract? If you still want the contract, you should send that acceptance letter overnight!

Remember Special UCC Rules

As stated previously, under common law, an acceptance must follow the mirror image rule, and any changed or added terms are considered a rejection and a counteroffer. In contrast, the UCC has special rules under Article 2 that deal with any contract disputes. For example, when a contract is between merchants, conflicting terms are canceled out in the final agreement, and provisions are used to accommodate for any issues (unless stated otherwise in the offer or the offer is revoked within a reasonable time). On the other hand, when a contract involves at least one nonmerchant, any new terms are only considered proposed terms and are non-binding.

Speaking of merchants, it's also essential to understand the UCC's definition of a "merchant" to apply the "firm-offer rule." According to the UCC, "for purposes of the firm-offer rule, a merchant also includes any businessperson if the transaction is commercial in nature."This means that even if there is no consideration by the offeree, an offer cannot be revoked if it is made and signed by a merchant.

Tips on Damages for Breach of Contract

As you know from fundamental contract law, when there is a breach of contract, the default remedy is damages to compensate the non-breaching party. But which type of damages are appropriate? As with most answers in law, that depends on the situation. Damages are most frequently calculated based on the non-breaching party's expectation interests or the value they expect to gain without the breach in addition to any losses or expenses caused by the breach (consequential and incidental). However, if the expectation interests are too difficult to pinpoint, fallback damages (reliance, restitution, liquidation) may be awarded to restore the non-breaching party's position to what it was before the contract was formed.

Tips on Remedies When There is no Contract

You know what to do when there is a breach of contract, but what can be done when there was no enforceable contract in the first place? Contract law provides two methods to compensate the plaintiff in such cases. In order to identify which method to use, the key is to ask yourself: Did the defendant make a promise? Suppose the answer is yes, and the plaintiff relied on that promise to their detriment. In that case, they can recover reliance damages to restore the plaintiff's original position under the doctrine of promissory estoppel. On the other hand, if the defendant did not make a promise but accepted a benefit knowing that the plaintiff expected payment, the doctrine of quasi-contract can be used to provide restitution damages for the benefit's fair market value.

Know about highly tested issues

In addition to the aforementioned topics, there are several highly tested issues that also deserve your consideration when studying contracts for the MBE. For example, be sure to understand the difference between unilateral v. bilateral contracts, when to apply the knock-out rule v. the mirror image rule, when consideration is not necessary, how to create and terminate an offer and how to revoke goods.

Additionally, while we stated in the beginning that most MBE contract questions involve the common law, that should not lead you to neglect your study of the UCC law. Note that there will also be 6-7 questions regarding UCC Article 2, revised Article 1, and the fundamental differences between the UCC and the common law.

Practice

Even if you think you performed well in your contract law classes, the MBE contracts is deliberately difficult and designed to trick even the best students and test-takers by leading them to make the same common mistakes year after year. Therefore, the best preparation for the test is to practice following our steps and tips to work through sample contract questions, especially those released by the NCBE.

Contracts Law Sample Questions and Answers

Ready to put your contracts knowledge to the test? Here are a few sample contracts questions and explanations, starting with a UWorld sample question:

The owner of a new office building contracted with a well-known landscaper to design and install landscaping around the building for $30,000. The agreement was memorialized in writing, was signed by both parties, and called for a budget of $5,000 for trees, shrubs, sod, and materials. The contract required the landscaper to complete the work within six months. Due to an unexpected increase in the price of trees and shrubs, the landscaper abandoned the project and never completed any of the work.

Three years after the landscaper's deadline, the building owner sued the landscaper for breach of contract. In the jurisdiction, the statute of limitations for breach of a services contract is two years after the breach, and the statute of limitations for breach of a sale-of-goods contract is four years.

Can the owner recover damages from the landscaper?

- No, because the contract is divisible with respect to the services and goods, and the landscaper's breach is therefore subject to the two-year statute of limitations.

- No, because the contract primarily calls for services, and the landscaper's breach is therefore subject to the two-year statute of limitations.

- Yes, because the landscaper's breach was a result of an increase in the price of goods, and his breach is therefore subject to the four-year statute of limitations.

- Yes, because the landscaper's breach was willful, and he is therefore estopped from denying that his breach is subject to the four-year statute of limitations.

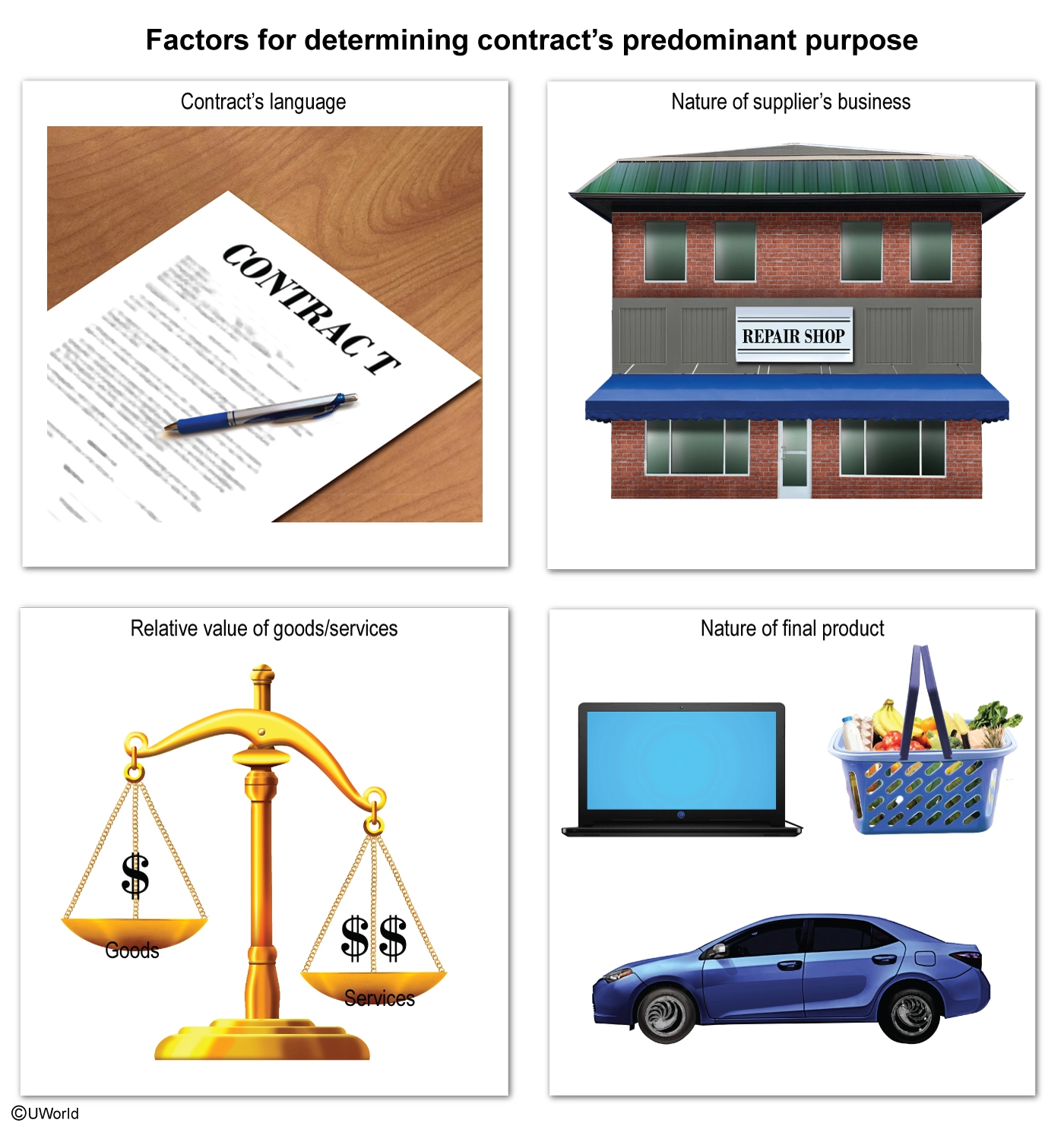

Contracts for the sale of goods are governed by Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), while contracts for services are governed by common law. However, some contracts involve the sale of goods and the rendering of services. To determine which law applies to a "mixed" or "hybrid" contract, courts ask whether its predominant purpose was the sale of goods or the rendering of services. The following factors are relevant to this determination:

- The contract's language

- The nature of the supplier's business (ie, whether it typically provides goods or services)

- The relative value of the goods and services

- The nature of the final product (ie, whether it can be described as a good or service)

Here, the building owner contracted to buy goods (eg, trees, shrubs, sod) and services (ie, designing and installing the landscaping). The owner likely hired the well-known landscaper due to his skill in performing landscaping services, and the $5,000 budget for goods was just one-sixth of the $30,000 contract price. Therefore, the contract primarily calls for services and is subject to the jurisdiction's two-year statute of limitations. And since the owner sued three years after the breach, the owner cannot recover damages from the landscaper.

(Choice A) The predominant-purpose test is unnecessary when a contract is divisible—ie, when the payment for goods can easily be separated from the payment for services. But here, the contract is likely indivisible since it combined the sale of the trees, shrubs, and sod with their installation.

(Choices C & D) The predominant-purpose test focuses on the parties' reason for entering the contract—not for breaching it. Therefore, it is irrelevant that the landscaper's breach was (1) a result of an increase in the price of goods or (2) willful.

Educational objective:

Sale-of-goods contracts are governed by the UCC, while services contracts are governed by common law. When a contract calls for the sale of goods AND the rendering of services, the contract's primary purpose determines whether the UCC or common law applies.

References:

- Bonebrake v. Cox, 499 F.2d 951, 960 (8th Cir. 1974) (applying the predominant-purpose test to determine which statute of limitations applies to a mixed contract for goods and services).

- Princess Cruises, Inc. v. Gen. Elec. Co., 143 F.3d 828, 833 (4th Cir. 1998) (listing factors that courts consider when applying the predominant-purpose test).

The owner of a gun store had been doing business with a hunter for many years. The hunter entered the gun store and spoke to the owner about purchasing a new hunting rifle on credit. The hunter disclosed that he intended to use the rifle on a turkey-hunting trip that weekend even though it was two weeks before turkey-hunting season began. The hunter left with the rifle after signing a written agreement to pay for the rifle in 12 monthly installments.

The rifle functioned well on the hunter's trip, during which a friend advised the hunter that he could avoid paying for the rifle because the contract was illegal. The hunter took the friend's advice and never paid any installments.

If the store owner sues for breach of contract, will he be likely to prevail?

- No, because the store owner knew that the hunter intended to use the rifle for an illegal purpose.

- Yes, because a contract to sell a rifle is not, in and of itself, illegal.

- Yes, because the store owner substantially performed and did not sell the rifle in order to further the hunter's illegal purpose.

- No, because the store owner failed to disaffirm the contract's illegal purpose before giving the hunter possession of the rifle.

| Recovery for breach of illegal Contract | |

|---|---|

| Expectation damages (full value of lost performance) |

|

| Restitution damages (reasonable value of benefit conferred) |

|

An illegal contract arises when one or both parties' purpose, formation, or performance is against the law. These contracts are usually void, and there is no recovery for breach. However, an exception arises if one party lacked an illegal purpose and substantially performed under the contract. That party may recover expectation damages for breach—even if he/she knew of the other party's illegal purpose.* This is true unless:

- the performing party took action to further the other party's illegal purpose or

- the illegal purpose involves grave social harm (eg, threat to human life).

Here, the contract was illegal because the hunter's purpose was to use the rifle to hunt outside the mandated turkey-hunting season. However, the store owner substantially performed by giving the hunter the rifle and had no illegal purpose of his own. And though the store owner knew of the hunter's illegal purpose, the store owner took no action to further it (Choice B). Additionally, hunting two weeks out of season does not involve grave social harm. Therefore, the store owner will likely prevail in a breach-of-contract suit.

*If the performing party was unaware of the other party's illegal purpose, then no further analysis is necessary.

(Choice A) The store owner did not need to disaffirm the contract's illegal purpose—eg, by telling the hunter not to use the rifle on the upcoming hunting trip. It is enough that the store owner did not act to further the hunter's illegal purpose and there was no threat of grave social harm.

(Choice C) A contract to sell a rifle is not, in and of itself, illegal (absent statutory restrictions—not seen here). But the contract is still illegal because the hunter intended to use the rifle for an illegal purpose.

Educational objective:

Illegal contracts are usually void and there is no recovery for breach. However, a party who substantially performed and lacked an illegal purpose may recover—even if he/she knew of the other party's illegal purpose—unless (1) the performing party took action to further that illegal purpose or (2) the purpose involves grave social harm.

- Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 182 (Am. Law Inst. 1981) (explaining the effect of performance under a contract when the other party's purpose is illegal).

A woman encountered her coworker and the coworker's friend at a local coffee shop. The woman, who knew that the coworker needed a new laptop for his personal use, had planned to offer her extra laptop to the coworker. The woman went to the counter to place her coffee order and, with her back to the table where the coworker and his friend sat, said, "By the way, I know you are looking for a new laptop. I will sell you my laptop for $100." The friend immediately replied, "I accept your offer!"

Has a contract been formed between the friend and the woman?

- No, because the friend was mistaken as to the terms of the contract.

- No, because the friend was not the party with whom the woman intended to contract.

- Yes, because the friend reasonably believed that he had the power to accept the woman's offer.

- Yes, because the woman's objective intent was to contract with whoever overheard the offer.

The offeror is master of the offer. This means, among other things, that the power to accept an offer belongs only to the person (or class of persons) with whom the offeror intended to contract. In contract law, intent is measured by an objective standard, not by the subjective intent or belief of a party. Therefore, whether the offeror intended to contract with someone is judged by outward objective facts, as they would be interpreted by a reasonable person.

Here, the woman knew that her coworker needed a new laptop. Her statement—"I know you are looking for a new laptop"—demonstrated her objective intent to contract with the coworker (Choice D). Although the friend overheard the woman's offer to sell her laptop, he could not reasonably believe that he had the power to accept it. This is especially true since there is no indication that the two had ever met (Choice C). Therefore, no contract was formed because the friend was not the party with whom the woman intended to contract.

(Choice A) A mistake as to a basic assumption upon which a contract was made renders the contract voidable—not void. If a contract is voidable, then it is considered valid until set aside. But here, no contract was ever formed because the offer was not accepted by the intended offeree, so this defense is inapplicable.

Educational objective:

The power of acceptance belongs only to the person(s) with whom the offeror intended to contract. Such intent is judged by outward objective facts, as interpreted by a reasonable person.

- Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 29 (Am. Law Inst. 1981) (to whom an offer is addressed).

Copyright © UWorld. All rights reserved.

Whether we like it or not, all of us can expect to encounter contracts at some point in our lives, so analyzing contracts is a great skill to master! We hope that our tips and steps to break down contract questions will help you conquer the contracts section on the MBE. Happy studying!

Frequently Asked Questions

How Many Contracts Questions on MBE?

There are 25 contracts questions on the MBE.

What Are the 6 Contracts Topics Covered on the MBE?

The six contracts topics covered on the MBE are: (1) formation of contracts; (2) performance, breach, and discharge; (3) defenses to contract enforceability; (4) parol evidence and interpretation; (5) contract remedies; and (6) third-party rights.

How Do You Answer Contract Questions?

To answer any contract question, always start by determining whether the situation falls under the UCC (for sale of goods) or the common law (for all the rest). Then, determine the main purpose of the contract, when it started, and the specific terms. These steps will help you determine the correct legal framework to apply to that scenario.

Is Contracts on the Multistate Essay Exam (MEE®)?

Maybe. While it’s not a guarantee, any legal topic, including contracts, could be a possible essay question on the MEE.

What are the Most Tested Topics in Contracts?

- 75% – based on common law

- 25% – contract formation

- 25% – performance, breach, and discharge

- 25% – focused on UCC Article 2 and revised Article 1

Other MBE Subjects

Related Blogs

Contracts questions on the MBE® fall into one of three categories: formation....

Read More »

You’ve known that a party can sue for breach of contract to enforce a ...

Read More »

At the outset, the mailbox rule seems pretty simple. You put something in ...

Read More »