The scope of torts encompasses a wide variety of situations, ranging from mere negligence to intentional harm. As a result, it is 1 of the fundamental subjects of the Multistate Bar Examination (MBE). Of the 175 scored multiple-choice questions, 25 are related to torts.

Torts Breakdown

To prepare for the MBE subject of Torts, it's essential to understand how this section is organized. The National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE®) has divided torts into 4 subtopics:

- Negligence

- Intentional Torts

- Strict Liability and Product Liability

- Other Torts

The most highly tested category is negligence, which comprises 50% of the torts questions (12-13 questions). The remaining 50% of the MBE torts questions are equally divided among the other categories, with 4-5 questions each for intentional torts, strict liability, product liability, and other torts.

| Torts Subtopics | Percent Tested | No. of Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Negligence | 50.0% | 12-13 |

| Intentional Torts | 16.7% | 4-5 |

| Strict Liability and Product Liability | 16.7% | 4-5 |

| Other Torts | 16.7% | 4-5 |

| Total scored questions for Torts | 25 | |

Negligence

Negligence constitutes 50% (12-13 questions) of Torts and accounts for 1/14th of your overall score on the MBE. Additionally, it is tested on most state exams, including the Multistate Essay Examination (MEE®).

To establish negligence, you must prove 4 main elements with evidence: duty, breach, causation, and harm. If even 1 of these elements is missing, it can serve as a basis for dismissal. For example, if someone slips and falls on a 2x4 left negligently on the sidewalk, but no harm occurs, there is no valid claim.

Duty is often 1 of the trickiest topics for test-takers. You must first determine whether the defendant owed the plaintiff a duty of care and whether that duty was reasonably breached. The expected duty of care varies depending on whether the defendant is a child, a mentally impaired individual, or a professional. For example, if the defendant is a child, the rule states that they owe a duty of care to a child of similar age, intelligence, and experience, acting under similar circumstances, unless they are engaged in an adult activity (e.g., shooting a gun or driving).

Similarly, in the cases of physician/patient, business owner/customer, employer/employee, legal guardian/minor, and carrier/passenger relationships, a duty to act arises when 1 party sees that the other is exposed to harm. However, there are instances where a defendant can be held liable for the actions of others — a concept known as vicarious liability — which commonly applies to employer/employee relations, parents of minor children, and animal owners.

Property owners are also held liable for any injuries that occur on their property. The level of duty owed depends on the type of owner and the classification of the visitor to their premises (invitee, licensee, or trespasser). The highest degree of duty and care is owed to invitees, such as customers, who are invited onto the premises for business activities. Under the law, property owners must provide a safe environment and disclose any hazards present, which is why many claims in these situations arise from slip and fall-accidents or falling objects. Conversely, there is little duty owed to a non-minor or an undiscovered trespasser.

Proving Negligence

To prove that the breach of duty caused actual and proximate harm, you must apply 2 tests to the scenario. First, use the "but-for" test to determine if the breach directly caused the harm. Ask yourself, but for the defendant's actions, would the harm have occurred? If the answer is yes, the harm did not directly result from the defendant’s actions or breach. Second, determine whether the harm was a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the breach and whether there was no unforeseeable, intervening, or superseding event that disrupted the chain of events from breach to harm.

When proof of fault or negligence is lacking, 2 legal doctrines may assist the plaintiff in seeking damages: negligence per se, which applies when the defendant has violated a statute designed to protect the plaintiff, and res ipsa loquitur, which allows negligence to be inferred from the surrounding circumstances.

Compensatory and Additional Damages

Once negligence has been proven, the injured party can recover compensatory damages equal to the fair market value of the losses incurred. Generally, these damages cover medical costs, property damage, and lost wages. However, it is also possible to recover additional compensation for intangible losses, such as emotional distress (although this is harder to prove), consortium for the victim's family, nominal damages, or punitive damages if the defendant's actions were particularly reckless. Furthermore, the defendant may be held responsible for a plaintiff's injuries even if they stem from a pre-existing condition, according to the eggshell skull or "thin skull" rule.

In cases involving multiple defendants, you must apply joint and several liability. In jurisdictions with joint and several liability, the plaintiff can recover damages from either or both defendants, regardless of their degree of fault. In contrast, in jurisdictions with pure several liability, a defendant can only be held liable for the maximum amount for which they were responsible.

Conversely, certain defenses can be applied to reduce or limit a defendant's liability for damages, such as contributory negligence, which attributes fault to the plaintiff. For instance, if a plaintiff is hit by a car while jaywalking, he is considered partly responsible for his injuries. Most states follow the rule of pure comparative negligence, which states that the recoverable damages will be reduced by the percentage of the plaintiff’s fault. Some states adopt a modified rule that bars a plaintiff from collecting damages if they are more than 50% liable. In contrast, a few states don't allow plaintiffs to recover damages if they are found to be even slightly negligent (1% or more).

The strongest defense against a negligence claim is based on the assumption of risk, which asserts that the plaintiff's participation implies their consent to the known dangers of the activity or their willingness to sign a liability waiver. This defense is commonly applied to claims arising from adventure or extreme sports and other risky activities.

Intentional Torts

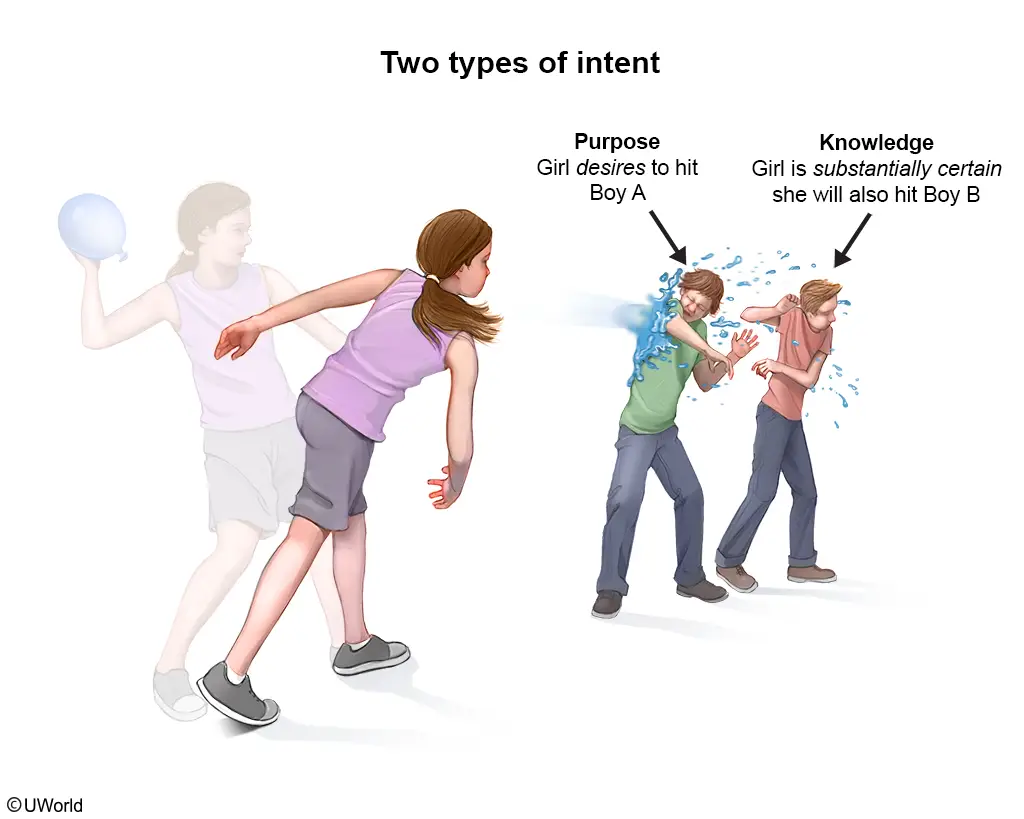

Be sure to prepare yourself for approximately 4-5 questions on intentional torts. To be held liable for an intentional tort, such as battery, assault, false imprisonment, intentional infliction of emotional distress, trespass to land, trespass to chattels, and conversion, you must demonstrate that the defendant had the intent or mindset to cause harm, rather than meerely exhibiting negligent behavior. There are 2 ways to prove intent:

- When the defendant acts to achieve specific results or

- When the defendant is certain that an act will lead to a particular outcome.

On the other hand, there are several viable defenses that a defendant may employ to escape liability in an intentional tort case. For example, common justifications include self-defense, the defense of property, and the defense of others. In these cases, the defendant must prove there was real and imminent danger and that using force, such as assault or battery, was the only reasonable way to stop it. Another common defense is the assertion of a special privilege or consent to act, such as parental discipline of a child, or explicit or implied consent through willing participation.

Strict Liability and Products Liability

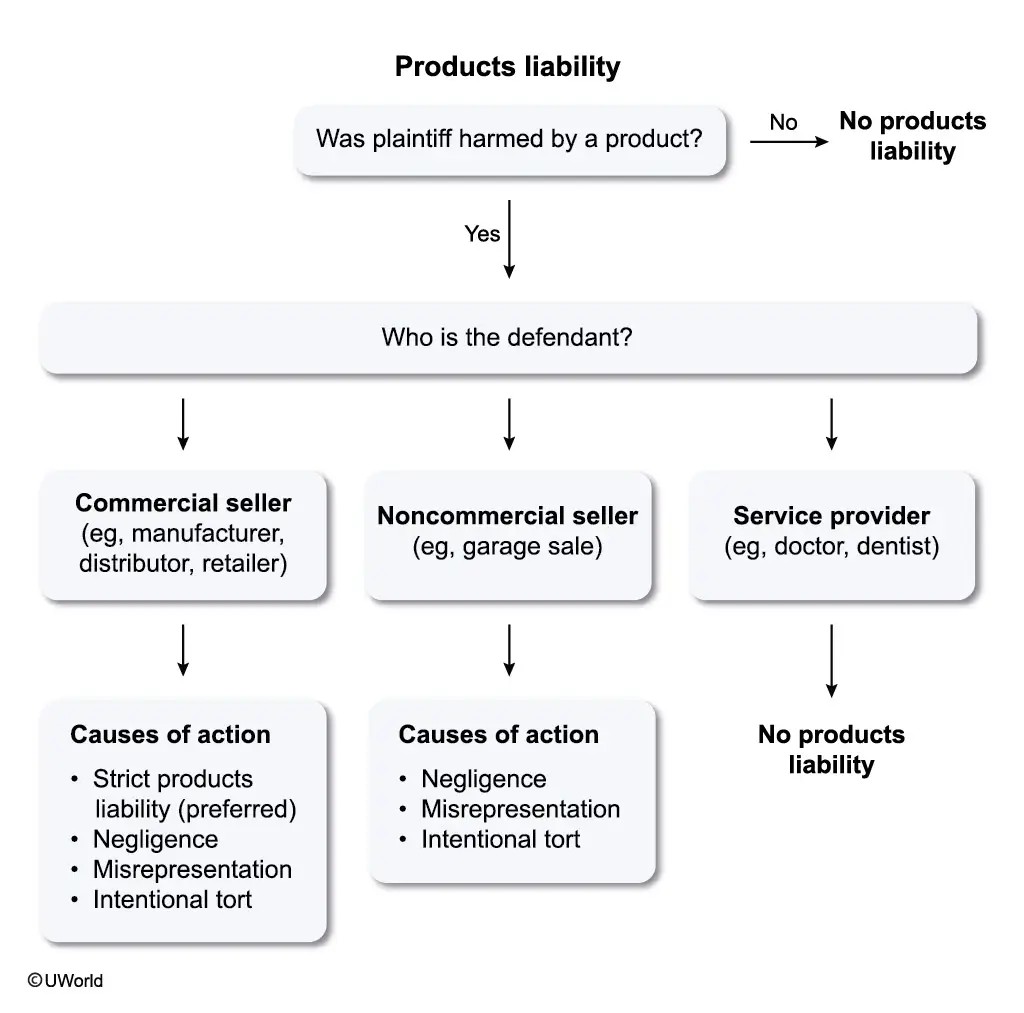

You should also expect to see about 4-5 tort questions on strict liability and product liability on the MBE. Strict liability allows a plaintiff to collect damages without proving negligence. Therefore, when it comes to strict liability, focus on the product rather than the defendant's actions. All a plaintiff needs to establish is duty, causation, and damages — not whether the defendant had good intentions, acted reasonably, or took precautions. Common situations involving strict liability include abnormally dangerous activities, wild animals, and product liability (excluding breach of warranty or negligence in some cases). Note that domesticated and farm animals do not fall under strict liability, even if they are known to have violent tendencies.

Other Torts

Additionally, there will be 4-5 tort questions based on other torts. The most commonly tested topics in this category include defamation, privacy torts (such as intrusion, appropriation, false light, and disclosure), and nuisance. The most nuanced type of these torts is defamation, which depends on whether the plaintiff is a private or public figure and the nature of the statement involved.

For example, if the plaintiff is a non-public figure and the issue is of public concern, the following elements must be established:

- A defamatory (false) statement about the plaintiff

- An unprivileged publication of the statement

- Negligence

- Damages

However, if the plaintiff is a public figure, the standard of fault must rise to the level of malice.

How to Study for Torts on the MBE

Now that you’ve had a chance to review the torts topics you’ll encounter on exam day, it’s time to devise a strategy to tackle torts questions with the following helpful tips:

Classify the Tort in Question

First, it’s a good idea to identify and classify the tort before reading the answer choices. This is simple when the facts are clearly presented in the call of the question. If the tort is not explicitly stated, however, you may need to look for clues in the rest of the question stem. Once you identify the tort (or torts) in question, you should recall their principal elements and common defenses.

Ask Yourself: What Would You Do?

The main question to ask regarding MBE torts is, how would a reasonable person behave in this situation? The answer will help you make 1 of the most challenging determinations in any torts case: Did the defendant owe the plaintiff a duty of care, and was that duty breached?

The Foreseeability Test

Next, ask, could I see this happening in real life because of this conduct, or did some other outside or unforeseen cause intervene? An example of a foreseeable result is hitting a parked car while texting and driving in a parking lot. In contrast, a piano falling on the roof of your vehicle is not foreseeable.

The situation can become more complicated when a chain of events leads to the final harm or injury. In that case, you must examine whether the foreseeability chain was broken or remained intact. For instance, if you were driving in a parking lot while texting and hit a parked car that had a dog in the front passenger seat, resulting in the dog’s death, it’s reasonable to think you should also be held liable for the dog’s death and the damage to the parked car. Conversely, if the dog were crushed by a falling piano, you wouldn’t be responsible for the dog’s death.

Tresspass vs. Conversion

Test-takers often confuse trespass and conversion, 2 types of intentional torts, because both involve the wrongful taking of personal property. A clear way to distinguish between the 2 is to consider the level of interference. For example, trespass to chattels involves minor interference, allowing the plaintiff to recover actual damages for repair costs and loss of use. In contrast, conversion results in significant interference, entitling the plaintiff to recover the full value of the chattel.

Products Liability

For any product liability claim, the plaintiff must prove that a product was defective when sold. The 3 types of defects include damage to a product during the manufacturing process, a design flaw in the overall product line that makes it dangerous, or a failure to warn consumers about any foreseeable and non-obvious risks associated with the product when used reasonably.

Know About Highly Tested Issues

Like the MBE, the most heavily tested torts topic on the MEE is negligence — alone or in conjunction with an employer's vicarious liability. Therefore, it's a good idea to spend more time studying the 4 essential elements needed for negligence claims, with an emphasis on the more complicated factors — duty, actual, and proximate cause. Other highly tested issues on the MEE include the eggshell skull rule, the duty of care expected of special populations, such as children; premises liability, depending on the type of visitor; strict liability rules, especially the requirements for a product liability claim; and how to apply the theory of negligence per se when a tort question presents a statute that establishes the duty of care.

Practice

Even if you feel confident about torts, it's important to remember that the tort questions on the MBE are meant to be challenging enough to mislead even the best students. Test-takers tend to make the same mistakes year after year. This is why the best preparation for the exam is to practice with tort questions and answer explanations in the UWorld MBE QBank.

Torts Sample Questions and Answers

Let’s try three Torts sample questions from UWorld’s MBE QBank:

A teenager was riding a bicycle when she saw a classmate walking toward her. The teenager rode quickly toward the classmate, knowing that he would think she would run into him on her current trajectory. The teenager was not purposefully trying to harm or touch him. The classmate saw the teenager riding toward him and yelled at her to stop. The teenager swerved at the last moment and avoided hitting him. The classmate had a panic attack because he thought that the teenager would hit him.

Is the classmate likely to succeed if he sues the teenager for assault?

| A. | No, because the teenager did not make contact with the classmate. | |

| B. | No, because the teenager did not purposefully try to harm or touch the classmate. | |

| C. | Yes, because the teenager acted with the requisite intent. | |

| D. | Yes, because the teenager's conduct was extreme and outrageous. |

Assault occurs when (1) a defendant intends to cause the plaintiff to anticipate an imminent, and harmful or offensive, contact with the plaintiff's person and (2) the defendant's affirmative conduct causes the plaintiff to anticipate such contact. The intent requirement is met when the defendant acts with either:

- purpose – the desire to cause anticipation of an imminent harmful or offensive contact or

- knowledge – the substantial certainty that the plaintiff will suffer such anticipation.

Here, the teenager rode her bicycle directly at her classmate, causing him to think that she would hit him (anticipation of imminent contact). And since the teenager knew with substantial certainty that the classmate would think she would run into him, she acted with the requisite intent. As a result, the classmate is likely to succeed in a suit against the teenager for assault.

(Choice A) Assault merely requires that the plaintiff be placed in anticipation of imminent contact. Actual bodily contact is not required. Therefore, the fact that the teenager did not make contact with the classmate is irrelevant.

(Choice B) The intent to make contact with the plaintiff is a requirement for battery, but assault merely requires the intent to cause the plaintiff to anticipate imminent contact. Therefore, the fact that the teenager did not purposefully try to harm or touch the classmate does not absolve her of liability for assault.

(Choice D) Extreme and outrageous conduct (i.e., conduct that is unacceptable in civilized society) is an element of intentional infliction of emotional distress—not assault, which only requires intentional conduct.

Educational objective:

For assault, intent exists when a defendant acts with the purpose (desire) or knowledge (substantial certainty) that his/her conduct will cause the plaintiff to anticipate an imminent, and harmful or offensive, contact.

- Restatement (Third) of Torts: Intentional Torts to Persons § 105 (Am. L. Inst., Tentative Draft No. 1, 2015) (providing the elements for assault).

A mother went to a retail toy store to purchase a birthday gift for her eight-year-old daughter. Without inspecting it, a toy-store employee sold an electric toy oven to the mother. The toy oven could bake small batches of real food using heat generated from light bulbs located in the interior of the oven. The instructions that came with the toy oven clearly stated that adult supervision was required when operating the oven, so the mother helped the daughter use the oven to bake brownies. While the brownies were baking, a six-year-old boy who lived next door came over to play with the daughter. When the brownies were done baking, the mother allowed the boy to open the oven and remove them. As he was doing so, a broken light bulb inside of the oven suddenly caught on fire, causing second-degree burns on the boy's hands.

The boy's father subsequently filed a negligence action against the manufacturer of the toy oven. At trial, it was established that had the manufacturer or the toy store exercised reasonable care in the inspection of the toy oven, the broken light bulb would have been discovered.

Who is likely to prevail?

| A. | The boy's father, because the manufacturer breached its duty of reasonable care toward the boy. | |

| B. | The boy's father, because the manufacturer is strictly liable for the toy oven's defect. | |

| C. | The manufacturer, because it was not reasonably foreseeable that the boy would be injured by the daughter's defective toy oven. | |

| D. | The manufacturer, because the toy store's negligent failure to inspect the toy oven before selling it to the mother is a superseding cause of the boy's injuries. |

A commercial manufacturer, distributor, retailer, or seller of a product owes a duty of reasonable care to any foreseeable plaintiff (ie, purchaser, user, bystander). Failure to exercise reasonable care in the inspection or sale of a product constitutes a breach of that duty. If the breach causes the plaintiff physical harm (ie, personal injury or property damage), the plaintiff will prevail in a negligence action.

Here, the manufacturer owed a duty of reasonable care to the boy as a user of the toy oven because it was foreseeable that other children might play with the daughter's toy (Choice C). Had the manufacturer exercised reasonable care in the inspection of the oven, it would have discovered the broken light bulb and the boy would not have suffered second-degree burns. Therefore, the boy's father will prevail because the manufacturer breached its duty of reasonable care toward the boy and caused his injuries.

(Choice B) A strict products liability action requires proof that the product was defective, the defect existed when it left the defendant's control, and the defect caused the plaintiff's injuries. But here, the father filed a negligence action—not a strict products liability action.

(Choice D) The toy store's failure to inspect the toy oven before selling it to the mother is not a superseding cause that would relieve the manufacturer of liability for the boy's harm. That is because the toy store's failure to inspect the toy oven was foreseeable.

Educational objective:

Commercial manufacturers, distributors, retailers, and sellers of a product owe a duty of reasonable care to any foreseeable plaintiff (ie, purchaser, user, or bystander). The failure to exercise reasonable care in the inspection or sale of a product constitutes a breach of that duty.

- Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 15 (Am. Law Inst. 1998) (failure

A pregnant woman, whose due date for the delivery of her viable fetus was less than a month away, was walking in a parking lot and looking at her cell phone. She was hit by a car driven by a police officer, who had just received word of an emergency and carelessly failed to see the woman. Several days later, the woman gave birth to a child who suffered neurological damage as a result of the accident.

The woman, on behalf of her child, brought a negligence suit against the police officer for damages associated with the physical injuries suffered by the child. The woman and the police officer were found to be equally at fault for the accident.

The jurisdiction has adopted a modified comparative fault statute that bars a plaintiff from recovery against a defendant whose fault is less than or equal to that of the plaintiff.

In the child's suit against the police officer, will the child be likely to recover for her injuries?

| A. | No, because the child was in utero at the time of the accident. | |

| B. | No, because the firefighters' rule applies to police officers. | |

| C. | Yes, because the child was viable at the time of the accident. | |

| D. | Yes, because the woman was not at greater fault than the police officer. |

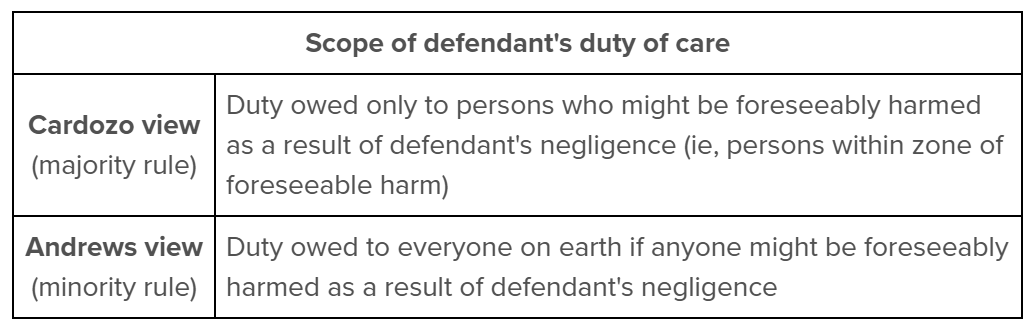

To recover in a negligence action, the plaintiff must establish four elements: duty, breach, causation, and damages. The majority rule is that the defendant owes a duty of care to the plaintiff only if the plaintiff is a member of the class of persons who might be foreseeably harmed as a result of the defendant's negligent conduct (sometimes called "foreseeable plaintiffs"). If a pregnant woman is a member of this class, then a duty is also owed to her unborn child—but only if the fetus was viable at the time the injury occurred.

Here, the police officer owed a duty of care to the pregnant woman because it was foreseeable that someone in the parking lot might be harmed by the police officer's negligent driving. As a result, the police officer also owed a duty to the woman's child, who was unborn (ie, in utero) but viable at the time of the accident (Choice A). And since the police officer breached that duty by carelessly failing to see the woman and caused the child's neurological damage, the child can recover from the police officer for her injuries.*

*The result would be the same under the minority rule (Andrews view) because the scope of duty under this rule is much broader—it extends to everyone if anyone might be foreseeably harmed.

(Choice B) Although the firefighters' rule applies to police officers (and other emergency professionals), it does not excuse their negligence. Instead, it bars emergency professionals from recovering damages for injuries attributable to the special dangers of their job.

(Choice D) The woman and the police officer were equally at fault for the accident. So had the woman been the plaintiff, she could not recover under this jurisdiction's modified comparative fault statute. But the plaintiff in this action is the child—not the woman. And since a negligent parent's fault is not imputed (ie, assigned) to a child plaintiff in a suit against a third party, the woman's relative fault is of no consequence here.

Educational objective:

Under the majority rule, a duty of care is owed to any person who might be foreseeably harmed by the defendant's negligent conduct. Additionally, any duty to a pregnant woman is also a duty to her unborn, viable child.

- Restatement (Second) of Torts § 281, cmt. c (Am. Law Inst. 1965) (explaining that an actor can only be negligent toward the class of persons who might be foreseeably harmed by his/her conduct).

Frequently Answered Questions

What are the 4 Torts topics covered on the MBE?

The 4 tort topics are: negligence, intentional torts, strict liability & product liability, and other torts.

How many torts questions are on the MBE?

Out of 175 scored multiple-choice questions, 25 will be about torts.

Is Torts on the MEE?

Yes, Torts is regularly tested on the MEE, either on its own or in combination with agency. The most highly tested MEE torts topic is negligence, followed by topics such as negligence per se, strict liability, and premises liability.