In 2016, The DC Bar Exam became the 20th jurisdiction to adopt the Uniform Bar Exam (UBE®) format. The National Conference of Bar Examiners is responsible for coordinating the UBE, which consists of the Multistate Essay Examination (MEE®), the Multistate Performance Test (MPT®), and the Multistate Bar Examination (MBE®). As such, the Washington DC Bar Exam is uniformly administered, graded, and scored, making examinees' scores more easily transferable to participating jurisdictions.

Taking the exam and preparing your application is a serious undertaking. Fortunately, this article provides everything you need to know, including the information about admission, pass rates, results, scoring and grading, format, and of course, the DC bar exam application process.

Note: The bar application period for DC is March 1–31, but per their release, concurrent applications can be filed from April 1–30. For more information, click here.

DC Bar Exam Structure

The Washington DC Bar Exam consists of the MPT, MEE, and MBE. Like all UBE jurisdictions, the DC Bar Exam is conducted twice a year, in February and July—specifically, the last consecutive Tuesday and Wednesday in February and July.

The DC Bar Exam assesses examinees' knowledge and understanding of general legal principles, factual analysis, legal analysis and reasoning, and communication skills to evaluate their competencies and readiness to practice law in any jurisdiction.

| Exam Sessions | Exam Component | Format & Hours |

|---|---|---|

| Tuesday Morning | MPT | 2 Items, 3 Hours |

| Tuesday Afternoon | MEE | 6 Essays, 3 Hours |

| Wednesday Morning | MBE | 100 Questions, 3 Hours |

| Wednesday Afternoon | MBE | 100 Questions, 3 Hours |

Multistate Performance Test (MPT)

The MPT is weighted at 20% and presents test-takers with a simulated case file based on a realistic scenario with a packet of various legal materials.

Examinees will show their lawyering skills using the materials provided to respond to the assignment(s). These assignments frequently involve law not tested on the bar exam (e.g., Professional Responsibility). Examinees will have to answer two such cases in 90 minutes each for a testing time of three hours.

Multistate Essay Exam (MEE)

The MEE is taken in the afternoon of the first day. It consists of six 30-minute essay questions and has a weight of 30%.

Multistate Bar Exam (MBE)

On the second day, examinees will have six hours to complete 200 multiple-choice questions (MCQs) on the MBE, which consists of two 3-hour sessions (morning and afternoon) testing 100 MCQs. The weightage of the MBE is 50%.

DC Bar Exam Requirements, Dates, and Scheduling

*IMPORTANT FEBRUARY 2025 BAR EXAM ANNOUNCEMENT*

Please note: New DC registration dates:

- Opens: November 16, 2024

- Closes: November 21, 2024

A government shutdown, per the D.C. Courts' plan, could severely impact admissions office operations and staffing. Early registration is advised. Please see the announcement here.

As a UBE jurisdiction, DC accepts valid UBE scores from other recognized jurisdictions. For other UBE jurisdictions and their deadlines, refer to their official websites. Ensure timely registration to avoid complications.

Make sure to schedule the requisite application deadline for your test. Washington DC does not have a late filing period, so if you miss the deadline, you cannot sit for the bar exam.

Requirements

Washington DC requires bar examinees to have a JD or LL.B from an ABA-approved law school. Applicants with a JD or LL.B from a non-ABA-approved law school may be accepted if they have completed 26 credit hours in a program with academic standards and a duration commensurate with ABA-approved programs.

Furthermore, they must have completed a minimum of 83 credit hours of law courses, experiential learning, out-of-class work, co-curricular activities, or some combination of these. Applicants without a JD or LL.B from an ABA-approved law school should read the DC Committee on Admissions memo for more details.

Exam Dates

Unlike other jurisdictions, Washington DC hasn’t had an official application closing date. Instead, closing occurs once all seats are filled. However, this has changed with the February 2023 exam. The application period is from November 16- 21, 2024. There is no late registration period. If you miss the deadline you cannot sit for the DC Bar Exam.

Please take note of the following relevant DC exam dates, location, and filing fees:

| Examination Dates | February 25-26, 2025 July 29-30, 2025 |

| Examination Location | DC Armory 2001 E Capitol St SE Washington DC, 20003 |

| Examination Fee | $232.00 NCBE investigation fee |

| Re-Take Only | $232.00 |

| Filing Period | Nov. 16 - 21, 2024 |

Scheduling

To schedule your Washington DC Bar Exam, you must first create an account, complete eligibility screening requirements, and fill out the electronic application. You will then be prompted to pay your application fee with credit or debit card, or e-check, no other form of payment is accepted. After completing the filing process you must complete supplemental forms and additional documentation. Details here.

DC Bar Exam Costs and Fees

| Application Type | Cost* | Exam Software Fee |

|---|---|---|

| First-Time Takers (non-attorneys) |

$405 | $150 |

| Attorneys | $405 | $150 |

| Re-take only | $405 | $150 |

| Applications for Admission Without Examination | Cost* |

|---|---|

| Motion by 3-Year Provision (non-attorneys) |

$418 |

| UBE Score Transfer | $418 |

| Special Legal Consultant | $450 |

Payment Policies

All payments must be submitted online with a credit card, debit card, or e-check. No other forms of payment will be accepted. Bank card transactions come with a 2.5% non-refundable transaction fee; E-checks have a non-refundable transaction fee of $1.00.

Cost-Saving Options

Law school is expensive enough; that’s why it’s imperative that graduating law students and law school graduates explore available resources to minimize costs related to the bar exam. From bar study loans to bar exam scholarships, we have compiled a list of financial aid options for you to consider:

Bar Study by American University Washington College of Law (AUWCL)

Students who need additional financial aid to register and prepare for the DC Bar exam can elect to apply for private bar study loans. Bar study loans are meant to help you finance expenses such as exam fees, bar application fees, and bar preparation fees. Certified by AUWCL, these loans tend to be capped at $15,000, but this amount can vary depending on the jurisdiction where you will sit for the bar exam. For more information, visit AUWCL’s Bar Study web page.Hispanic Bar Association of the District of Columbia (HBA-DC)

Describing itself as “a local voluntary bar association in the District committed to the advancement and progress of Latinos in the legal profession,” HBA-DCl awards $5,000 scholarships through its HBA-DC Foundation. Students may use the scholarship to cover tuition, books, and bar exam fees while enrolled and in good standing in their final year pursuing a Juris Doctor at an ABA-approved law school in Washington, DC For more information, check out the HBA-DC Foundation website.The American Bar Association (ABA)

The American Bar Association (ABA) compiles a list of diversity scholarships for law school students with disabilities at all three levels. If you are a student with a disability and would like to apply for scholarships to assist with your bar exam costs, be sure to review and bookmark this valuable resource.

DC Bar Exam Subjects & Topics

The Washington DC Bar Exam is formatted according to the UBE. It consists of a written section on day one (MEE/MPT) and a 200 multiple choice question exam (MBE) on day two. Below is a detailed breakdown of each portion of the exam.

Testable Subjects on the MEE

Business Associations are nearly always tested on the MEE. You’ll want to brush up on the principles of agency as they relate to business relationships. Below is an outline of the subject.

- Agency relationships

- Power of agent to bind principal

- Vicarious liability of principal for acts of agent

- Fiduciary duties between principal and agent

- Creation of partnerships

- Power and liability of partners

- Rights of partners among themselves

- Dissolution

- Special rules concerning limited partnerships

- Corporations and Limited Liability Companies

- Formation of organizations

- Pre-organization transactions

- Piercing the veil

- Financing the organization

- Management and control

If you confront Civil Procedure on the exam, assume that the sections of Title 28 of the US Code pertaining to trial appellate jurisdiction, venue, and transfer, are in effect, along with the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

This subject has been tested often over the past ten years. Increase your odds by targeting the theoretical basis of the rules and the distinctions between personal matter and subject matter. See below for an overview of Civil Procedure.

- Jurisdiction and venue

- Law applied by federal courts

- Pretrial procedures

- Jury trials

- Motions

- Verdicts and judgments

- Appealability and review

Conflict of Law questions frequently relate to the Klaxon Doctrine, recognition of marriage, full faith and credit clause, real and personal property, mergers, dissenters’ rights, foreign corporations, and transfer to a more appropriate forum.

It is the least tested UBE subject, and questions are always combined with other subjects, especially Civil Procedure, Family Law, Descendants Estate, and Corporations/LLCs.

- Domicile

- Jurisdiction of courts

- Choice of law

- Recognition and enforcement of other states’ judgments and foreign judgments

Examinees will likely confront Contracts on its own. Focus your studies on contract formation and performance obligations, and assume that articles 1 and 2 of the UCC are in effect. Here is a topic breakdown.

- Formation of contracts

- Defenses to enforceability

- Contract content and meaning

- Performance, breach, and discharge

- Remedies

- Third-party rights

Criminal Law and Procedure frequently appears on the MEE and typically tests issues regarding the defense of insanity, the Fifth and Fourth Amendments, and homicide. Review definitions of common concepts (e.g., “malice aforethought in murder, “Miranda warnings,” “Interrogation,” and “Custody”). See the topic breakdown below.

- Homicide

- Other crimes

- Inchoate crimes; parties

- General principles

- Constitutional protection of accused persons

Evidence is tested every year. It typically appears on its own but has been seen with Criminal Procedure on past MEEs. Commonly tested issues are hearsay and impeachment. Character evidence, relevancy, witness testimony, and policy exclusions are also essential to review. See the outline below.

- Presentation of evidence

- Relevancy and reasons for excluding relevant evidence

- Privileges and other policy exclusions

- Writings, recording, and photographs

- Hearsay and circumstances of its admissibility

The Uniform Interstate Family Support Act (UIFSA) and the Uniform Child Custody Jurisdiction and Enforcement Act (UCCJEA) are typically applied to issues of Family Law. You may see this subject appear with Conflict of Laws issues, but it is more often tested on its own. See the outline below for details.

- Getting married

- Being married

- Separation, divorce, dissolution, and annulment

- Child custody

- Rights of unmarried cohabitants

- Parent, child, and state

- Adoption

- Alternatives to adoption

Real Property frequently appears alongside other subjects and is tested about every year. Brush up on deeds, recording acts, landlord-tenant law, and essential definitions (e.g., warranty deed, merger, quitclaim deed, etc.). Below is a topic breakdown.

- Ownership of real property

- Rights in real property

- Real estate contracts

- Mortgages/security devices

- Titles

Torts will most likely be on your MEE. It’s been a favorite of those who create the exam for some time. It typically appears with Agencies regarding the vicarious liability of an employer. Review basic tort principles, negligence, children and duty, eggshell-skull rule, premises liability, negligence per se, and strict liability.

Examinees should assume survival actions and claims for wrongful death are available. Assume that relevant rules are joint unless stated. See the topic outline below.

- Intentional torts

- Negligence

- Strict liability and products liability

- Other torts

The MEE frequently features Trusts and Estates, and issues often regard validity, revocability, types of trusts, pour-over will, discretionary trusts, and charitable trusts.

- Descendants’ Estates

- Wills

- Family protection

- Living wills and durable health care powers

- Trusts

- Future interests

- Construction problems

The NCBE has stated that you should assume the Official Texts of Articles 1 and 9 of the UCC are in effect if you confront this subject on the exam. Secured Transactions have appeared with Contracts and Sales, and Real Property, but it is more often independent. Review the four types of goods, attachment and perfection.

- General UCC principles

- Applicability and definitions

- Validity of security agreements and rights of parties

- Right of third parties; perfected and unperfected security interests; rules of priority

- Default

Note: Even though there are six essays, more than six subjects can be tested. In other words, a single fact pattern may have questions that implicate one or more different areas of the law. For instance, in the July 2020 UBE, Corporations was tested with Constitutional Law. With that being said, not all subjects are tested evenly.

While Civil Procedure is also tested on the MBE, it is the most frequently tested subject on the MEE. Since February 2014, Civil Procedure has been tested more than 71% of the time (either as a component or an entire essay). During this period, the top 5 most frequently tested subjects on the MEE have been:

- Civil Procedure (71%);

- Contracts (59%);

- Real Property (59%);

- Constitutional Law (53%); and

- Secured Transactions (53%)

Testable Subjects on the MBE

The MBE tests examinees across the following subjects in 200 multiple-choice questions lasting six hours:

- Contracts

- Constitutional Law

- Criminal Law and Procedure

- Civil Procedure

- Evidence

- Real Property

- Torts

Out of the 200 questions, 25 questions are considered to be “experimental” questions for future bar exams. The other 175 questions are divided evenly so that 25 questions are counted toward your score for each subject. In other words, there would be 25 scored Contracts questions on the MBE.

UWorld MBE Sample Questions

Quality speaks for itself. Try some of our free MBE sample questions below.

A husband and wife were married in State A and lived there for 10 years before separating. One month later, the wife permanently moved to State B and immediately filed for divorce in a federal court in State B. The wife claims that she is entitled to $300,000 in alimony. The husband appeared in the action and has filed a motion to dismiss for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction.

Should the court grant the motion?

- No, because the court has diversity jurisdiction over the case.

- No, because the husband waived a subject-matter jurisdiction challenge by appearing in the case.

- Yes, because state courts have exclusive jurisdiction over this type of action.

- Yes, because the wife did not establish a domicile in State B.

Explanation:

| Federal diversity jurisdiction exceptions |

|

Federal courts cannot exercise diversity jurisdiction over cases involving:

|

A federal court must possess subject-matter jurisdiction to hear the merits of a case before it. Subject-matter jurisdiction can be established through either:

- federal-question jurisdiction – when a claim arises under the U.S. Constitution, a treaty, or federal law (not seen here) or

- diversity jurisdiction – when the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000 and the opposing parties are citizens of different states.

Here, diversity jurisdiction is established since the wife claims that she is entitled to $300,000 and the parties are citizens of different states (States A and B). However, federal courts cannot exercise diversity jurisdiction over cases involving probate matters or domestic relations. Instead, state courts have exclusive jurisdiction over these types of actions (Choice A).* Therefore, the husband's motion to dismiss should be granted.

(Choice B) A challenge to subject-matter jurisdiction is never waived. However, a challenge to personal jurisdiction is waived if the defendant has voluntarily appeared in the case, unless it was a special appearance for the express purpose of objecting to personal jurisdiction.

(Choice D) An individual is a citizen of the state where he/she is domiciled—ie, physically present with the intent to remain indefinitely. Since the wife permanently moved to State B, she has established her domicile there.

Educational objective:

Federal courts cannot exercise diversity

jurisdiction over cases involving probate matters or domestic relations. Instead, state courts

have exclusive jurisdiction over these types of cases.

Bluebook Citations :

- Ankenbrandt v. Richards, 504 U.S. 689, 703–04 (1992) (explaining the domestic-relations exception to diversity jurisdiction).

A congressional committee investigated the pharmaceutical industry and found that the high cost of prescription drugs purchased and sold in the United States negatively impacted the nation's economy and the health of its citizens. In response, Congress passed a statute that regulates "the retail prices of every purchase or sale of prescription drugs in the United States."

A group of pharmaceutical companies challenged the constitutionality of this statute in federal court.

What is the strongest argument in support of the constitutionality of this statute?

- Congress may enact statutes for the general welfare.

- Congress may regulate the prices of all domestic purchases and sales of goods.

- The Constitution grants Congress the power to regulate the interstate transportation of prescription drugs.

- The purchases and sales of prescription drugs in the United States substantially impact interstate commerce in the aggregate.

Explanation:

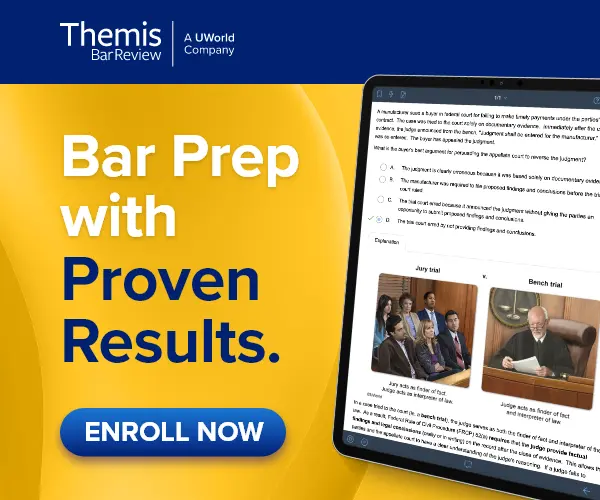

The commerce clause gives Congress broad power to regulate interstate and foreign commerce. This includes:

- the channels of interstate and foreign commerce (eg, roadways)

- the instrumentalities of interstate and foreign commerce (eg, vehicles)

- persons and things moving in interstate or foreign commerce (eg, goods and services) and

- in-state activities that, singly or in the aggregate, substantially impact interstate or foreign commerce.

Since Congress's commerce power is broad, federal statutes are constitutional if there is any rational basis for concluding that the regulated activity substantially affects interstate or foreign commerce. This can be shown through express congressional findings.

Here, the federal statute regulates the retail prices of prescription drugs in the United States. Congress has the authority to regulate such products' interstate transportation, but this statute also regulates in-state purchases and sales (Choice C). Since the congressional committee found that the high cost of prescription drugs negatively impacted the nation's economy, it is rational to conclude that their aggregated in-state purchases and sales substantially impact interstate commerce. Therefore, this is the strongest argument to support this statute.

(Choice A) The taxing and spending clause empowers Congress to tax and spend for the general welfare. But regulating prices is not equivalent to taxing or spending.

(Choice B) Congress cannot regulate the prices of every domestic purchase and sale of goods since it cannot regulate purely in-state sales that do not substantially affect interstate commerce.

Educational objective:

The commerce clause empowers Congress to regulate (1)

channels and instrumentalities of, (2) persons and things moving in, and (3) in-state activities

that—singly or in the aggregate—substantially affect interstate or foreign commerce.

Bluebook Citations :

- Gonzales v. Raich, 545 U.S. 1, 17 (2005) (explaining Congress's broad authority under the commerce clause).

The owner of a new office building contracted with a well-known landscaper to design and install landscaping around the building for $30,000. The agreement was memorialized in writing, was signed by both parties, and called for a budget of $5,000 for trees, shrubs, sod, and materials. The contract required the landscaper to complete the work within six months. Due to an unexpected increase in the price of trees and shrubs, the landscaper abandoned the project and never completed any of the work.

Three years after the landscaper's deadline, the building owner sued the landscaper for breach of contract. In the jurisdiction, the statute of limitations for breach of a services contract is two years after the breach, and the statute of limitations for breach of a sale-of-goods contract is four years.

Can the owner recover damages from the landscaper?

- No, because the contract is divisible with respect to the services and goods, and the landscaper's breach is therefore subject to the two-year statute of limitations.

- No, because the contract primarily calls for services, and the landscaper's breach is therefore subject to the two-year statute of limitations.

- Yes, because the landscaper's breach was a result of an increase in the price of goods, and his breach is therefore subject to the four-year statute of limitations.

- Yes, because the landscaper's breach was willful, and he is therefore estopped from denying that his breach is subject to the four-year statute of limitations.

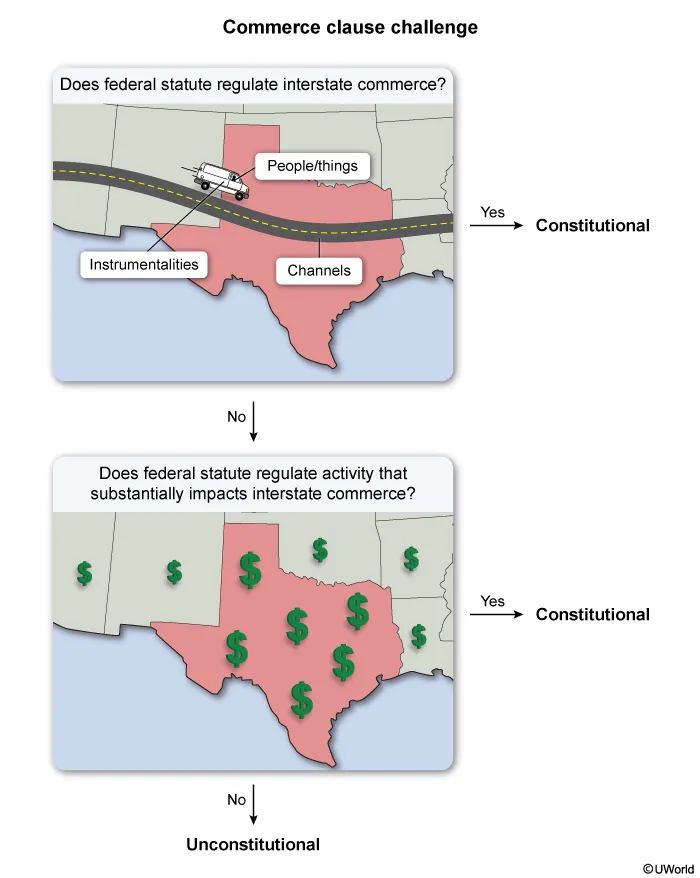

Contracts for the sale of goods are governed by Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), while contracts for services are governed by common law. However, some contracts involve the sale of goods and the rendering of services. To determine which law applies to a "mixed" or "hybrid" contract, courts ask whether its predominant purpose was the sale of goods or the rendering of services. The following factors are relevant to this determination:

- The contract's language

- The nature of the supplier's business (ie, whether it typically provides goods or services)

- The relative value of the goods and services

- The nature of the final product (ie, whether it can be described as a good or service)

Here, the building owner contracted to buy goods (eg, trees, shrubs, sod) and services (ie, designing and installing the landscaping). The owner likely hired the well-known landscaper due to his skill in performing landscaping services, and the $5,000 budget for goods was just one-sixth of the $30,000 contract price. Therefore, the contract primarily calls for services and is subject to the jurisdiction's two-year statute of limitations. And since the owner sued three years after the breach, the owner cannot recover damages from the landscaper.

(Choice A) The predominant-purpose test is unnecessary when a contract is divisible—ie, when the payment for goods can easily be separated from the payment for services. But here, the contract is likely indivisible since it combined the sale of the trees, shrubs, and sod with their installation.

(Choices C & D) The predominant-purpose test focuses on the parties' reason for entering the contract—not for breaching it. Therefore, it is irrelevant that the landscaper's breach was (1) a result of an increase in the price of goods or (2) willful.

Educational objective:

Sale-of-goods contracts are governed by the UCC,

while services contracts are governed by common law. When a contract calls for the sale of goods

AND the rendering of services, the contract's primary purpose determines whether the UCC or

common law applies.

Bluebook Citations :

- Bonebrake v. Cox, 499 F.2d 951, 960 (8th Cir. 1974) (applying the predominant-purpose test to determine which statute of limitations applies to a mixed contract for goods and services).

- Princess Cruises, Inc. v. Gen. Elec. Co., 143 F.3d 828, 833 (4th Cir. 1998) (listing factors that courts consider when applying the predominant-purpose test).

A man and a woman dated for several weeks. During that time, the man repeatedly asked the woman to have sex. Each time, the woman responded that she would not have sex with the man unless they were married. One evening, the man promised the woman that they would elope the following weekend if she would agree to have sex. The woman agreed and the couple had sex. The following weekend, the man told the woman that he had no intention of eloping and only made that promise to get the woman's consent. The woman reported the man to the police, who later arrested and charged the man with rape.

Is the man guilty of rape?

- No, because fraud in factum did not negate the woman's consent.

- No, because fraud in the inducement did not negate the woman's consent.

- Yes, because the woman's consent was obtained by fraud in factum.

- Yes, because the woman's consent was obtained by fraud in the inducement.

Explanation:

| Consent to sexual intercourse obtained by fraud | ||

| Type of fraud | Definition | Effect |

| In factum |

|

Negates victim's consent |

| In inducement |

|

Does not negate victim's consent |

In most modern jurisdictions, rape is defined as sexual intercourse with another without that person's consent.* This means that rape did not occur if the victim consented to sexual intercourse. However, a victim's consent may be ineffective if it was obtained by fraud. There are two types of fraud:

- Fraud in factum – when consent is obtained by fraud regarding the nature of the act itself, leaving the victim unaware that he/she consented to sexual intercourse and negating the victim's consent

- Fraud in the inducement – when consent is obtained by fraud regarding what the victim knows is an act of sexual intercourse, which does not negate the victim's consent

As a result, consent obtained by fraud in factum is not a valid defense to rape, but consent obtained by fraud in the inducement is a valid defense.

Here, the man falsely promised the woman that they would elope if she agreed to have sex with him. Since the woman knew that the act to which she consented was sexual intercourse, her consent was obtained by fraud in the inducement (Choices A & C). This type of fraud did not negate the woman's consent, so the man is not guilty of rape (Choice D).

Educational objective:

Fraud in factum occurs when the fraud pertains to the nature of the act itself and negates a rape victim's consent. In contrast, fraud in the inducement occurs when fraud is used to gain consent to what the victim knows is an act of sexual intercourse and does not negate the victim's consent.

A plaintiff sued a defendant for negligence to recover damages that the plaintiff suffered as a result of a crash between the two parties. At trial, the plaintiff's attorney called the plaintiff's wife to testify as to what she witnessed on the day of the crash. On cross-examination of the wife, the defendant's lawyer elicited several responses that tended to show that the plaintiff's actions constituted contributory negligence. The plaintiff's attorney seeks to ask the wife several questions on redirect examination, but the defendant's attorney objected.

What is the strongest argument that the court must allow redirect examination of the wife?

- The plaintiff's attorney failed to provide all significant information on direct examination.

- The plaintiff's attorney seeks to reiterate the necessary elements of the claim.

- The plaintiff's attorney seeks to reply to all matters raised on cross-examination.

- The plaintiff's attorney seeks to reply to significant new matters raised on cross-examination.

Explanation:

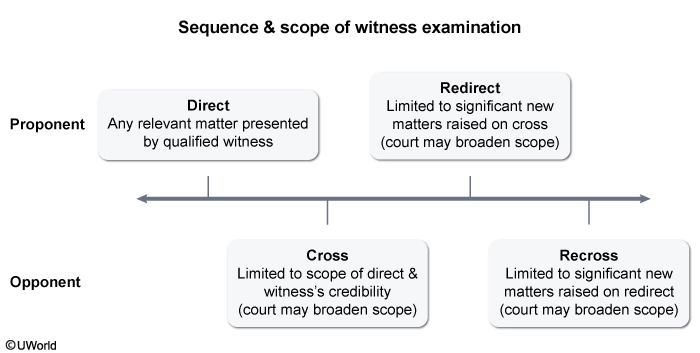

Federal Rule of Evidence 611 gives trial courts the authority to exercise reasonable control over the mode and order of examining witnesses at trial. This includes the discretion to determine whether—and to what extent—redirect examination of witnesses should be permitted. But when a party raises a significant new matter while cross-examining a witness, the court must allow the opposing party to address that matter through redirect examination.

Therefore, the strongest argument for allowing redirect examination of the plaintiff's wife is that the plaintiff's attorney seeks to reply to significant new matters that were raised on cross-examination.

(Choice A) A party is expected to elicit all significant information during direct examination of a witness. Therefore, a court need not permit redirect examination to allow the party to provide information inadvertently omitted on direct examination.

(Choices B & C) Redirect examination is generally limited to significant new matters raised on cross-examination. Therefore, a party is not entitled to redirect examination to (1) reiterate information like the necessary elements of the claim or (2) reply to all matters addressed in cross-examination.

Educational objective:

When a party raises a significant new matter on cross-examination of a witness, the court must allow redirect examination by the opposing party to address that matter.

Bluebook Citations :

- Fed. R. Evid. 611 (explaining the mode and order of examining witnesses).

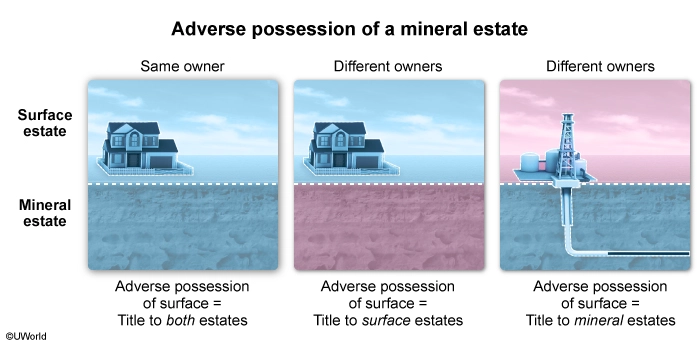

Twenty years ago, a man who owned a 20-acre ranch agreed to sell all of his mineral rights to his neighbor. The man executed a warranty deed conveying the mineral estate to the neighbor, who failed to record the deed.

The following year, a woman moved her mobile home onto an undeveloped five-acre portion of the man's ranch. After the woman had lived on the property for 10 years, a local drilling company began operations on a nearby tract to drill a natural gas well. Believing that the woman owned the property, the drilling company approached the woman about leasing the mineral rights on her property and requested that the woman sign a lease of her mineral rights. The woman signed the lease as requested, and it was promptly and properly recorded. The drilling operations were successful, and the drilling company prepared to distribute profits from royalties. However, a dispute arose between the neighbor and the woman, as both parties claim ownership of the minerals.

The period of time to acquire title by adverse possession in the jurisdiction is 10 years.

In an action to determine title, is the court likely to award title to the mineral estate to the woman?

- No, because the woman actually possessed only the surface estate that had previously been severed from the mineral estate.

- No, because the woman did not actually possess the mineral estate until she signed the lease of the mineral rights.

- Yes, because the neighbor failed to record the warranty deed conveying the mineral estate.

- Yes, because the woman adversely possessed both the surface estate and the mineral estate for the statutory period.

Explanation:

An adverse possessor can acquire title to land owned by another if his/her possession of the land is:

- Open and notorious – apparent or visible to a reasonable owner

- Continuous – uninterrupted for the statutory period

- Exclusive – not shared with the owner

- Actual – physical presence on the land and

- Nonpermissive – hostile and adverse to the owner.

If the surface and mineral estates are owned by the same party, then the adverse possessor will acquire title to both estates—even if only one estate is actually possessed. But if the mineral estate has been severed from the surface estate (ie, the surface and mineral estates are owned by different parties), then the adverse possessor will only acquire title to the estate that is actually possessed. The mineral estate is actually possessed when the adverse possessor mines or drills wells on the land.

Here, the neighbor purchased the mineral estate from the man, thereby severing the mineral estate from the surface estate. And since the woman merely lived on the property for the 10-year statutory period—she did not attempt to mine or drill a well on the mineral estate—she actually possessed only the surface estate during that time (Choice D). This means that the woman did not adversely possess the mineral estate, and the court is not likely to award her title to that estate.

(Choice B) Adverse possession of a mineral estate requires the commencement of drilling or mining operations. Merely signing a lease of the mineral rights is not enough.

(Choice C) A deed need not be recorded to be valid, so the neighbor's failure to record has no impact on whether the woman adversely possessed the mineral estate.

Educational objective:

If a mineral estate has previously been severed from the surface estate (ie, surface and minerals owned by different persons), then an adverse possessor can only acquire title to the mineral estate by actually possessing the minerals (eg, by mining or drilling wells).

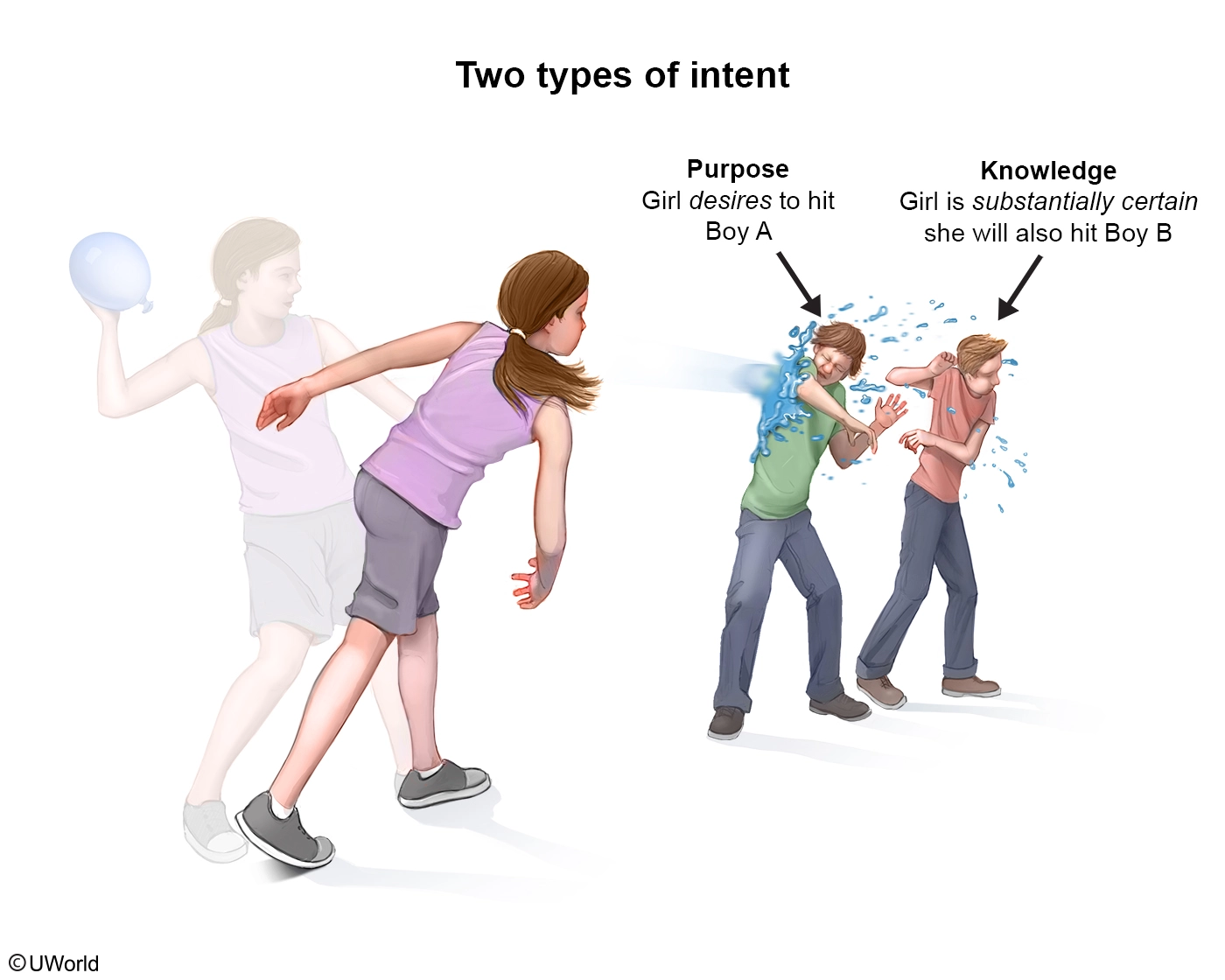

A teenager was riding a bicycle when she saw a classmate walking toward her. The teenager rode quickly toward the classmate, knowing that he would think she would run into him on her current trajectory. The teenager was not purposefully trying to harm or touch him. The classmate saw the teenager riding toward him and yelled at her to stop. The teenager swerved at the last moment and avoided hitting him. The classmate had a panic attack because he thought that the teenager would hit him.

Is the classmate likely to succeed if he sues the teenager for assault?

- No, because the teenager did not make contact with the classmate.

- No, because the teenager did not purposefully try to harm or touch the classmate.

- Yes, because the teenager acted with the requisite intent.

- Yes, because the teenager's conduct was extreme and outrageous.

Explanation:

Assault occurs when (1) a defendant intends to cause the plaintiff to anticipate an imminent, and harmful or offensive, contact with the plaintiff's person and (2) the defendant's affirmative conduct causes the plaintiff to anticipate such contact. The intent requirement is met when the defendant acts with either:

- purpose – the desire to cause anticipation of an imminent harmful or offensive contact or

- knowledge – the substantial certainty that the plaintiff will suffer such anticipation.

Here, the teenager rode her bicycle directly at her classmate, causing him to think that she would hit him (anticipation of imminent contact). And since the teenager knew with substantial certainty that the classmate would think she would run into him, she acted with the requisite intent. As a result, the classmate is likely to succeed in a suit against the teenager for assault.

(Choice A) Assault merely requires that the plaintiff be placed in anticipation of imminent contact. Actual bodily contact is not required. Therefore, the fact that the teenager did not make contact with the classmate is irrelevant.

(Choice B) The intent to make contact with the plaintiff is a requirement for battery, but assault merely requires the intent to cause the plaintiff to anticipate imminent contact. Therefore, the fact that the teenager did not purposefully try to harm or touch the classmate does not absolve her of liability for assault.

(Choice D) Extreme and outrageous conduct (i.e., conduct that is unacceptable in civilized society) is an element of intentional infliction of emotional distress—not assault, which only requires intentional conduct.

Educational objective:

For assault, intent exists when a defendant acts with the purpose (desire) or knowledge (substantial certainty) that his/her conduct will cause the plaintiff to anticipate an imminent, and harmful or offensive, contact.

- Restatement (Third) of Torts: Intentional Torts to Persons § 105 (Am. L. Inst., Tentative Draft No. 1, 2015) (providing the elements for assault).

Take a look at a typical competitor sample question below. Their practice questions might parody the exam, but ours consistently meet or exceed exam-level difficulty. Their limited explanations address the right answer choice but do not go the extra mile to explain the wrong choices – so you don’t make the same mistakes on exam day.

A mother gave her land to her two kids, a son, and a daughter, as joint tenants. The son built two adjoining homes on the land. He lived in one house and rented the other. The daughter lived out of the country and never visited the land. The daughter needed money, so she sold her interest in the land to her ex-boyfriend. Her ex-boyfriend immediately hired a developer to build a third home on the land. Soon after the daughter had sold her interest in the land, she was killed in a motorcycle accident. The ex-boyfriend is now asking the court for a judicial partition of the land. The son contends that upon his sister's death, he was now the sole owner of the land.

How should the court rule?

- For the ex-boyfriend, because he plans to live on the land.

- For the ex-boyfriend, because he paid for the son’s interest in the land.

- For the son, because he has the right of survivorship.

- For the son, because he has the sole position of the land.

Explanation:

Correct answer: B

DC Bar Exam Scoring/Grading

The passing score for the UBE in Washington DC is 266 out of 400. The UBE is divided into two sections, the written section (MEE/MPT) and the multiple choice section (MBE). Each section measures performance on a scaled score out of 200. Therefore, a scaled score of 133 on each section would add to a successful score of 266. However, you can get a 125, for example, on one section and a 141 on the other and still pass the UBE. Here is a breakdown of the weight of each of the three portions of the exam:

- MEE (30%) : 6 essays worth 6-points each.

- MPT (20%) : 2 tasks worth 6 points each.

- MBE (50%) : 200 multiple-choice questions. Each is worth 1 point; 25 are not scored.

Your MEE, MPT, and MBE raw scores are all converted into scaled scores via a statistical method known as equating. This is done to ensure fairness across exam versions. Bonuses or penalties are given based on the relative difficulty of your particular exam version. For example, you may get 133 answers correct on the MBE, but your scaled score could be 125 if your exam version is deemed less difficult than others.

DC MPRE Minimum Passing Score

You can become licensed in DC by achieving an MPRE score of 75 or higher either before or after you sit for the bar exam. Unlike many other jurisdictions, DC does not have a time limit for when a score becomes “stale.” In other words, you could use an MPRE score you achieved more than five years prior to applying for licensure in DC.

Transferring UBE score to and from DC

By July 2022, there will be 40 jurisdictions that administer the Uniform Bar Exam (UBE). Because each jurisdiction is ultimately responsible for the policies they enact for attorney licensure, each UBE jurisdiction has agreed to administer the same exam and accept the validity of the other jurisdictions’ UBE scores.

As a result, applicants who’ve sat for the UBE in one jurisdiction can transfer their score from that jurisdiction to other UBE jurisdictions to become licensed in them. However, each jurisdiction sets its own minimum score that an applicant would need to achieve. In other words, you can pass in one UBE jurisdiction but not pass in another UBE jurisdiction.

As long as you get the minimum passing score in your target jurisdiction(s), you can transfer your UBE score to become licensed (subject to other requirements imposed by the target jurisdiction(s), e.g., Character and Fitness). Here’s a table with information about the minimum UBE score for each jurisdiction:

| Minimum UBE Score | Jurisdiction(s) |

|---|---|

| 260 | Alabama, Minnesota, Missouri, New Mexico, North Dakota |

| 264 | Indiana, Oklahoma |

| 266 | Connecticut, District of Columbia, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Montana, New Jersey, New York, South Carolina, Virgin Islands |

| 270 | Arkansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, Wyoming |

| 272 | Idaho |

| 273 | Arizona |

| 276 | Colorado, Rhode Island |

| 280 | Alaska |

*Note that Pennsylvania has not yet announced what their minimum UBE score will be. Since DC is a UBE jurisdiction and has agreed with all other UBE jurisdictions to accept the UBE scores of each others’ examinees, you can transfer your DC UBE score to become licensed in other UBE jurisdictions. You may also use the UBE score from another UBE jurisdiction to become licensed in DC, provided that you have at least the minimum score for the target jurisdiction.

If you are transferring from another jurisdiction to DC, your score would have to be at least 266. To transfer a UBE score, you would have to electronically submit a request for UBE score services through your NCBE Account and pay the transfer fee. You would also follow the target jurisdiction’s application process.

What is the time limit for accepting a transferred UBE score in DC?

You may transfer your UBE score from another jurisdiction to DC for bar admission as long as you do so within five years of obtaining a passing score. Other jurisdictions may be the same length of time or shorter. Here is a table with the maximum score age (the time limit for accepting the transferred UBE score) for each UBE jurisdiction:

| Maximum Age of Transferred UBE Score | Jurisdiction(s) |

|---|---|

| 2 years | North Dakota, Rhode Island |

| 2 years/5 years* | Iowa, Texas |

| 25 months | Alabama |

| 3 years | Arkansas, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, South Carolina, Virgin Islands, West Virginia, Wyoming |

| 3 years/5 years* | Colorado, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont |

| 37 months | Idaho |

| 40 months | Washington |

| 4 years | Illinois |

| 5 years | Alaska, Arizona, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, Ohio |

DC Bar Exam Pass Rates

While DC has had low pass rates in the past decade, pass rates have been rising since its first UBE administration in July 2016. Out of the 606 applicants that sat for the February 2023 DC Bar Exam, only 271 have passed, representing a 45% overall pass rate. Below are the pass rates for the DC Bar Exam over the past several years:

| Exam | First Timers | Repeaters | Overall | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | No Of Candidates | Pass Rate | No Of Candidates | Pass Rate | No Of Candidates | Pass Rate |

| 2022 | 1595 | 76% | 411 | 27% | 2006 | 66% |

| 2021 | 1901 | 81% | 964 | 40% | 2865 | 67% |

| 2020 | 1829 | 73% | 664 | 40% | 2493 | 57% |

| 2019 | 1905 | 73% | 679 | 36% | 2584 | 63% |

DC Bar Exam Results

The Committee on Admissions typically releases DC Bar Exam results within 9-10 weeks of the exam date. You may check your results by visiting their website.

DC Bar Exam for Foreigners

Unlike most jurisdictions, DC permits foreign-trained attorneys to become licensed initially with a DC Bar License. However, below are a few other things that you should know about:

- 26 Credits in Bar-Subject-Focused Courses

- Additional Application Difference

- Special Legal Consultant

Firstly, unless a foreign-trained attorney or foreign LL.M has been awarded a J.D. or LL.B. from an ABA-accredited law school, they must have completed at least 26 credit hours at an ABA-accredited law school in UBE bar-subject-focused courses. Some examples of courses that would likely qualify would be criminal law, criminal procedure, contracts, professional responsibility, or business associations.

In addition to the application components that ABA-accredited law school graduates need to complete, LL.M applicants must also submit the following documents:

- Declaration of Graduation from a non-ABA-Approved Law School

- Declaration of Completion/Anticipated Completion of 26 Credit Hours at an ABA-Approved Law School

- Copy of Diploma from non-ABA-Approved Law School

- Copy of Official Transcripts from non-ABA-Approved Law School

- Copy of Official Transcripts from ABA-Approved Law School

- Copy of Course Descriptions from ABA-Approved Law School

The “ABA-Approved Law School” would be the school where you received or are in the process of obtaining your LL.M. On the other hand, “non-ABA-Approved Law School” is where you received your initial law degree (unless it is an ABA-Approved Law School).

In general, this type of license allows a foreign-licensed attorney to establish an office in DC to practice their licensed jurisdiction’s law. However, this licensure does not permit one to practice US law, as defined under DCCA Rules 46(f)(6) and 49(b).

While the application mechanics are similar to full DC licensure, there are some differences. The following is a non-exhaustive list of the most significant differences:

- No MPRE requirement

- Proof of ability to practice in your licensed jurisdiction

- Evidence of being 26 years or older

- Summary of laws and customs to demonstrate how a DC licensed attorney would be able to establish offices and give legal advice to clients in the foreign jurisdiction within which you are licensed to practice

Foreign Law Students without a first degree in law cannot sit for the Washington DC Bar exam.

What Makes DC Bar Licensure Process Unique?

DC has a jurisdiction-specific component that examinees must complete. Upon admission to the DC Bar, all applicants must complete a mandatory course on DC Rules of Professional Conduct and DC Practice within 12 months of admission to the DC Bar.

DC’s rules provide for Admission on Motion, meaning an attorney licensed in other jurisdictions can be admitted into the DC bar without taking the DC Bar Exam when they have been a member of any other bar of any state or territory of the United States in good standing for at least three years immediately preceding the filing of the application.

Themis is the only bar review company that routinely publishes its nationwide first-time taker pass rates without filters, and Themis is now an official member of the UWorld Family. When you sign up for Themis + UWorld full bar review, you get one integrated system that includes everything you need to pass the bar. Here are some of the highlights:

- 4,000+ MBE questions (including recently released NCBE-licensed questions)

- 100+ practice essays from past Multistate Essay Exams

- Short on-demand lectures with corresponding handouts

- Comprehensive outlines

- 20 Multistate Performance Test questions from previously administered bar exams

- Content curated by a team of legal experts and professionals

Contact Details of DC State Bar

The District of Columbia Court of Appeals is open from Monday through Friday from 8:30 am to 5 pm. Phone operating hours are as follows:

- Monday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday — 8:30 am to 11:00 am and 3:00 pm to 5:00 pm

- Tuesday 8:30 am to 9:30 am; 11:00 am to noon and 3:00 pm to 5:00 pm

Questions regarding application status must be made through your District of Columbia Court of Appeals account. All other inquiries can be made as tabulated below.

| District of Columbia Court of Appeals Contact Information | |

|---|---|

| General Information |

[email protected] |

| Upcoming Bar Exam Accommodation Questions | [email protected] |

| Foreign Trained Applicants without a first law degree from an ABA approved school | [email protected] |

| Address |

DC Court of Appeals, Room123 |

DC Bar Exam FAQs

How often is the DC Bar Exam offered?

How long Is the Bar Exam in DC?

Can anyone take the Bar Exam in DC?

How hard Is the DC Bar Exam?

What are DC Bar Exam application deadlines and fees?

What is the minimum passing UBE score for DC?

How much does it cost to retake the DC Bar Exam?

How many times can I take the DC Bar Exam?

Can you practice law without a law degree in DC?

I was unsuccessful; am I able to review my MEE and MPT submissions?

Does DC allow concurrent application for admission by transferring UBE score?

Does DC offer reciprocity with any jurisdiction?

How Long Does it Take to Study for the DC Bar Exam?

It takes 400 hours to study for the DC Bar Exam. Most students cram these hours in 8-10 weeks before their exam, but if you’re looking for a more moderate schedule, start 4 months out (about 20 hours a week).