Whenever legal disputes arise — whether between individuals, businesses, or organizations — Civil Procedure guides any lawsuits through the court system. If the thought of navigating these rules makes you anxious, you’re not alone. With the right approach, however, mastering Civil Procedure can be far more manageable than it seems.

The NCBE has divided Civil Procedure into 7 categories:

| Civil Procedure Topics | % Tested | Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Jurisdiction and Venue | 22.2% | 5-6 |

| Law Applied by Federal Courts | 8.3% | 2-3 |

| Pretrial Procedures | 22.2% | 5-6 |

| Motions | 22.2% | 5-6 |

| Jury Trials | 8.3% | 2-3 |

| Verdicts and Judgments | 8.3% | 2-3 |

| Appealability and Review | 8.3% | 2-3 |

*Source1

Civil Procedure by Topic, Weightage and Tested Questions

Not all Civil Procedure topics carry the same weight on the MBE. Some are more likely to show up than others. A hefty 66.6% of the questions focus on just 3 areas: Jurisdiction and Venue, Pretrial Procedures, and Motions. Each of these topics typically accounts for 5 to 6 questions. The remaining 4 categories — Law Applied by Federal Courts, Jury Trials, Verdicts and Judgments, and Appealability and Review — make up the remaining 33.3%, with 2 to 3 questions each.¹

Understanding this breakdown allows you to prioritize the areas that matter most, helping you focus your prep time where it counts.

Jurisdiction and Venue / State Law in Federal Court

You can expect 5-6 questions on Jurisdiction and Venue, which often relate to the foundational concepts you learned in your first-year law classes. An initial determination in any case is whether it belongs in state or federal court.

State courts generally have broader subject-matter jurisdiction, hearing mostly cases involving individuals, contracts, torts, or state laws. Federal courts, in contrast, handle a narrower range of cases, including those involving the U.S. Constitution or federal law (federal-question jurisdiction), bankruptcy, or disputes between states or foreign governments.2

An important exception to this is diversity jurisdiction, which applies if 2 conditions are met3:

- The opposing parties must reside in different states

- The amount in controversy must exceed $75,000

Federal courts may also assert supplemental jurisdiction over related state law claims if they arise from the same case or controversy as a federal claim.

Personal jurisdiction is another consideration. A court cannot exercise this authority unless the defendant has sufficient “minimum contacts” with the state, such as living, incorporating, or conducting business there.4 The plaintiff must also properly serve the defendant according to state law, either where the court sits or where the defendant resides. While personal jurisdiction can be waived or transferred, subject-matter jurisdiction is non-negotiable.

Service of process also varies depending on the court. State courts have unique rules for notifying defendants, so attention to detail is crucial. In federal cases, service can be carried out by any nonparty over the age of 18 using the SAID method: State law method, Agent, Individual, and Dwelling.

Law Applied by Federal Courts

When a case is in federal court, 1 of the first questions to address is whether federal common law or state law applies. This concept is commonly tested on the MBE, with 2-3 questions typically devoted to it.

In cases where a federal court sits in diversity, it must apply the substantive law of the state in which it is located, including that state’s conflict of laws rules. Procedural matters, however, are governed by federal common law.5 While this distinction might seem clear-cut, determining whether an issue is substantive or procedural can be challenging. Substantive issues impact the rights and duties of the parties, while procedural matters dictate how the case is conducted.

When in doubt, the Erie Doctrine provides essential guidance. It resolves conflicts between state and federal law in diversity cases and helps clarify whether state or federal law should govern. We’ll explore this doctrine in greater depth in the study strategies section.3

Pretrial Procedures

Once jurisdiction and applicable law are determined, the next phase is Pretrial Procedures — the foundation for how a case proceeds. This stage begins with filing the complaint, serving the defendant, and addressing preliminary matters such as injunctions, pleadings, joinders, discovery, and pretrial conferences. Expect to encounter 5-6 questions on this topic, with a strong emphasis on timing. Deadlines play a pivotal role, and creating a structured timeline can help you stay on track.6

Pretrial Procedures introduce a range of legal terms, many of which relate to joinders — the process of adding claims or parties. Claims can be introduced through counterclaims or cross-claims, while additional parties may be joined through permissive joinder, impleader, intervention, or interpleader. Understanding the distinctions between these terms is essential for navigating procedural questions on the MBE.

The primary goal during the pretrial stage is to resolve as many issues as possible before heading to trial, reducing costs and streamlining the legal process. Courts encourage parties to exchange evidence and disclosures early, allowing for settlements or narrowing down the contested issues. In cases where no genuine disputes of material fact exist, courts may issue rulings without proceeding to trial.

Motions

Motions account for roughly 20% of the questions on the MBE, translating to about 5-6 questions. Knowing when and how to file a motion is essential, as they often come with specific deadlines (much like pleadings). Building a timeline for each stage of litigation can help ensure nothing falls through the cracks.7

Motions are formal, written requests asking the court to issue a ruling at 3 key points in the litigation process: pretrial, during trial, and post-trial.

- Pretrial Motions: Two of the most common motions filed before trial are motions to dismiss and motions for summary judgment. A motion to dismiss argues there’s no legal basis for the case to proceed, while a motion for summary judgment requests the court to decide based on the law, bypassing the need for a trial entirely.8 If the defense is challenging personal jurisdiction, insufficient service of process, or improper venue, the motion must be filed promptly — typically after the first responsive pleading.9

- Motions During Trial: The primary motion at this stage is judgment as a matter of law (JMOL). This motion asks the judge to rule in favor of 1 party on the grounds that the opposing party lacks sufficient evidence to persuade the jury.

- Post-Trial Motions: After the trial concludes, parties can file motions to address errors made during the proceedings or to contest the court’s ruling. This might include a motion for relief from judgment or a request for a new trial if issues like a lack of subject matter jurisdiction are discovered.

A thorough understanding of motions and their timing can significantly improve your ability to answer these questions on the exam.

Jury Trials

Jury Trials may seem straightforward, but they can present nuanced questions on the MBE. You can expect to encounter 2-3 questions covering the right to a jury trial, jury selection, and instructions.

The Seventh Amendment guarantees the right to a jury trial in civil cases where the amount in controversy exceeds $20.10 To exercise this right, a party must formally request a jury trial by serving a written demand to the opposing party. This demand must be made within 14 days after the last pleading is filed, ensuring all parties have adequate time to adjust their litigation strategy.

Jury selection, known as voir dire, allows the judge and attorneys to question prospective jurors to assess their impartiality. Both sides can eliminate jurors in 2 ways:

- For Cause: Jurors can be struck if they have a clear interest in the case or demonstrate bias.

- Peremptory Challenge: Each side may remove up to 3 jurors without stating a reason, provided the removal isn’t based on race or gender.11

Once jury instructions are delivered, any objections must be raised immediately. Failing to object on the spot may waive the right to challenge the instructions on appeal.

Verdicts and Judgments

Expect to see 2-3 questions addressing what unfolds after a verdict or judgment is reached. This portion of Civil Procedure covers key concepts like default judgments, jury verdicts, judicial findings, and preclusion doctrines.

A common pitfall for test-takers is misunderstanding the difference between default and default judgment. A default occurs when the defendant fails to respond within the required timeframe, but this doesn’t automatically hand victory to the plaintiff. For the case to conclude in their favor, the plaintiff must file a motion for default judgment and obtain the court’s approval.

Once a final judgment is entered, 2 doctrines — res judicata and collateral estoppel — prevent re-litigation of settled matters:

- Res Judicata (Claim Preclusion): This doctrine bars parties (or their privies) from bringing a new claim based on the same transaction or occurrence after a final judgment. It ensures that once a case is decided, it cannot be refiled by the same parties in the same roles.

- Collateral Estoppel (Issue Preclusion): While res judicata addresses entire claims, collateral estoppel narrows the focus to individual issues. If a particular issue was already litigated and essential to the outcome of a prior case, that issue cannot be reargued in a new proceeding.12

Appealability and Review

You can expect 2-3 questions on Appealability and Review. While final judgments are generally the only appealable orders, the NCBE frequently tests the exceptions. In certain jurisdictions, appeals may be allowed for temporary orders, collateral judgments, or cases involving unresolved claims or parties. Orders granting or denying a judgment notwithstanding the verdict (JNOV), directed verdict, or motion for a new trial may also be subject to appeal.

Additionally, questions may focus on the standards appellate courts apply when reviewing cases. Legal questions are reviewed de novo, factual determinations are examined for clear error, and discretionary rulings are assessed under the abuse of discretion standard.

California’s Transition to New Multiple Choice Questions

Starting in February 2025, California will introduce a significant change to its bar exam by replacing the traditional NCBE multiple-choice questions with a new set developed by Kaplan.13 While the shift may raise concerns, the core legal principles tested across the seven primary bar exam subjects will remain unchanged.

The overall format will be familiar — 200 questions spread across four 90-minute sessions.13 The primary difference will lie in the source of the questions, not the content or scope. According to the State Bar of California, studying with MBE materials will remain beneficial, as the same analytical skills will be required. Whether testing remotely or in person, the updated exam structure reflects California’s effort to modernize the process without altering its essential framework.

How to Study for Civil Procedure on the MBE and MEE

Studying Civil Procedure for the MBE and MEE is manageable with the right approach. By applying a few proven strategies, you can break down even the most challenging Civil Procedure questions and improve your confidence heading into exam day.

Identify the Call of the Question

As with any MBE question, the first step is identifying exactly what a question is asking. While this may seem straightforward, test-makers often disguise the call of the question within the fact pattern, sometimes a few sentences beyond the initial stem. Civil Procedure issues can overlap with other areas of law, so be vigilant. A question that appears to focus on torts, for instance, may actually hinge on venue or jurisdiction. Carefully reading through the details and pinpointing the underlying procedural issue can prevent you from being misled by surface-level facts.

Use the Chunking Method

Civil Procedure is packed with deadlines, making it one of the more detail-heavy subjects to memorize. The good news is that there’s a simple strategy to make this easier — chunking. By grouping related deadlines and concepts into smaller, meaningful clusters, you can reduce mental overload and retain information more effectively. The key is to focus on the 6 essential deadlines that frequently appear on the exam.

Chunking can also help organize other areas of Civil Procedure. For example, motions can be divided into pretrial, during trial, and post-trial categories, making them easier to recall under pressure. While there are plenty of ready-made charts and resources available, creating your own customized versions can significantly enhance retention and help solidify your understanding of the material.

When to Apply the Erie Doctrine

The Erie Doctrine can be far less intimidating once you break it down. While the MBE frequently tests this topic, the good news is that it applies in only 1 scenario — when a federal court sits in diversity and must decide whether to apply state or federal law.

In most cases, the distinction is straightforward. Federal law governs procedural matters, such as filing deadlines and court processes, while state law controls substantive issues that influence individual rights and obligations. The challenge arises when federal and state laws conflict or when the distinction between procedural and substantive isn’t immediately clear. In these instances, start with a federal rule analysis to see if a federal statute or rule directly applies. If the issue relates to procedural housekeeping rather than legal rights, federal law typically governs. Otherwise, the Erie analysis dictates that state law prevails, particularly if applying federal law would incentivize forum shopping or create an inequitable result for one party.

When to Apply Supplemental Jurisdiction

Supplemental jurisdiction allows a federal court to hear additional claims related to a case already under its jurisdiction, provided those claims arise from the same case or controversy. This principle is most commonly applied when the court has original jurisdiction based on either federal question or diversity jurisdiction. If the primary claim involves a federal question, the court has the discretion to extend its authority to state law claims that would not independently meet federal jurisdiction requirements.14

However, when original jurisdiction is based on diversity, the rules are more restrictive. Supplemental jurisdiction cannot apply to additional claims that fail to meet diversity requirements or fall short of the $75,000 amount in controversy. This safeguard ensures that smaller claims cannot bypass federal diversity thresholds by attaching themselves to larger cases.

How to Earn Maximum Points on the MEE

MEE graders generally prefer answers that begin with a broad rule or basic principle before narrowing down to specific rules or exceptions. The most effective way to achieve this is by using the IRAC format:

Issue: Identify the issue at hand

Rule: Explain the rules (general to specific)

Analysis: Apply the specific rules to solve the issue

Conclusion: Explain why the rule was chosen

Don't let yourself get burned out. While it's imperative to study enough, it's just as important to give your brain a rest.

Learn and Memorize the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

In addition to mastering the dense content of Civil Procedure, it’s important to develop a strong working memory of the 11 primary Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, as amended on December 1, 2020.15 These rules form the foundation of procedural law and are essential for understanding how cases are managed and resolved in federal court:

- Scope and Purpose

- One Form of Action

- Commencing an Action

- Summons

- Serving and Filing Pleadings and Other Papers

- Computing and Extending Time; Time for Motion Papers

- Pleadings Allowed; Form of Motions and Other Papers

- General Rules of Pleading

- Pleading Special Matters

- Form of Pleadings

- Signing Pleadings, Motions, and Other Papers; Representations to the Court; Sanctions

Know About Highly Tested Issues on the MEE

Civil Procedure remains the most frequently tested topic on the MEE, making preparation for examiners’ favorite areas essential. Jurisdiction and venue are consistently among the most tested topics, with a particular focus on when to apply diversity and supplemental jurisdiction. Federal question and personal jurisdiction often appear together, and a strong approach to personal jurisdiction questions involves referencing the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause while distinguishing between general and specific jurisdiction.

Questions on venue and forum transfer are also common, requiring knowledge of when a federal court can transfer a case to another forum with proper subject-matter jurisdiction, especially when convenience or justice necessitates the change. Other frequently tested issues include methods of serving a defendant, known as the SAID method, and the factors for issuing preliminary injunctions or temporary restraining orders to preserve the status quo. Questions may also cover permissive joinder, which requires plaintiffs to show that claims arise from the same transaction and involve related legal issues.

Practice

Mastery of Civil Procedure requires more than simply selecting the correct answer — it’s about articulating why that answer is correct. The MBE is known for its curveballs, often testing your understanding of the rules and your ability to navigate exceptions. Consistent practice, especially with questions released by the NCBE, is key to preparing for these challenges. These practice problems mirror the complexity and nuance of the questions you’ll encounter on the exam.

Equally important is practicing full MEE responses. Using the IRAC method — identifying the issue, stating the rule, applying the law, and concluding — helps you build a clear and effective structure under exam conditions. This process boosts your MEE performance and deepens your overall understanding of Civil Procedure, making you more confident on exam day.

Civil Procedure Sample Questions and Answers

Think you’re prepared to tackle Civil Procedure on the bar exam? Below is a sample question from UWorld’s Civil Procedure bank, carefully crafted to mirror the style and complexity of NCBE questions:

A husband and wife were married in State A and lived there for 10 years before separating. One month later, the wife permanently moved to State B and immediately filed for divorce in a federal court in State B. The wife claims that she is entitled to $300,000 in alimony. The husband appeared in the action and has filed a motion to dismiss for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction.

Should the court grant the motion?

| A. | No, because the court has diversity jurisdiction over the case | |

| B. | No, because the husband waived a subject-matter jurisdiction challenge by appearing in the case | |

| C. | Yes, because state courts have exclusive jurisdiction over this type of action | |

| D. | Yes, because the wife did not establish a domicile in State B |

| Federal diversity jurisdiction exceptions |

|---|

|

Federal courts cannot exercise diversity jurisdiction over cases involving:

|

A federal court must possess subject-matter jurisdiction to hear the merits of a case before it.

Subject-matter jurisdiction can be established through either:

- federal-question jurisdiction – when a claim arises under the U.S. Constitution, a treaty, or federal law (not seen here) or

- diversity jurisdiction – when the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000 and the opposing parties are citizens of different states.

Here, diversity jurisdiction is established since the wife claims that she is entitled to $300,000 and the parties are citizens of different states (States A and B). However, federal courts cannot exercise diversity jurisdiction over cases involving probate matters or domestic relations. Instead, state courts have exclusive jurisdiction over these types of actions (Choice A).*Therefore, the husband's motion to dismiss should be granted.

*The probate and domestic-relations exceptions exist because states have a strong interest in these substantive areas and are more qualified to deal with the constant judicial involvement these types of cases require.

(Choice B) A challenge to subject-matter jurisdiction is never waived. However, a challenge to personal jurisdiction is waived if the defendant has voluntarily appeared in the case, unless it was a special appearance for the express purpose of objecting to personal jurisdiction.

(Choice D) An individual is a citizen of the state where he/she is domiciled—ie, physically present with the intent to remain indefinitely. Since the wife permanently moved to State B, she has established her domicile there.

Educational objective:

Federal courts cannot exercise diversity jurisdiction over cases involving probate matters or domestic relations. Instead, state courts have exclusive jurisdiction over these types of cases.

References:

- Ankenbrandt v. Richards, 504 U.S. 689, 703–04 (1992) (explaining the domestic-relations exception to diversity jurisdiction).

A pharmaceutical company sued its competitor for patent infringement in federal court. The competitor's attorney hired a pharmacist to examine the case and testify as an expert at trial. The pharmacist studied the case and submitted an initial draft of her report to the attorney. After reading the draft report, the attorney noticed that certain facts and data were missing. To correct this issue, the attorney emailed the pharmacist and provided additional facts and data to include in the report. The pharmacist then revised her report based on this additional information.

After receiving this revised report from the competitor's attorney, the pharmaceutical company served a request for production on the attorney to produce the email exchanged with the pharmacist.

Must the attorney produce the email?

| A. | No, because attorney communications with expert witnesses are privileged. | |

| B. | No, because the contents of the email are discoverable through interrogatories served on the pharmacist. | |

| C. | Yes, because a draft of an expert report is discoverable. | |

| D. | Yes, because the email contained facts and data that the pharmacist relied on to revise her report. |

| Discovery of expert materials (FRCP 26(b)(4)) |

|

|---|---|

| Non Testifying expert |

|

| Testifying expert |

|

FRCP = Federal Rule of Civil Procedure.

Parties can use various discovery methods, including requests for production, to obtain nonprivileged information that is relevant to any claim or defense and proportional to the needs of the case. Materials held by an expert witness expected to testify at trial are discoverable with two exceptions:

- Drafts of expert reports or disclosures

- Privileged attorney-expert communications

All attorney-expert communications are privileged unless they (1) relate to the expert's compensation or (2) identify facts, data, or assumptions provided by the attorney that the expert considered or relied on in forming his/her opinions.

Here, the competitor's attorney hired the pharmacist to examine the case and testify as an expert at trial. After reading the pharmacist's draft report, the attorney emailed the pharmacist and provided her with additional facts and data that were missing in the draft. The pharmacist then relied on those facts and data to revise her report, so the email is not a privileged communication (Choice A). Therefore, the attorney must produce the email.

(Choice B) Interrogatories are a discovery request in which a party serves written questions on another party that inquire about any matter within the scope of discovery. However, interrogatories may not be served on a nonparty such as an expert expected to testify at trial. Therefore, the contents of the email are not discoverable through interrogatories served on the nonparty pharmacist.

(Choice C) Drafts of expert reports are not discoverable. Therefore, the attorney would not be required to produce the email on this basis.

Educational objective:

All attorney-expert communications are privileged unless they (1) relate to the expert's compensation or (2) identify facts, data, or assumptions provided by the attorney that the expert considered or relied on in forming his/her opinions.

References:

- Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(4) (discovery of expert materials).

A corporation has been the subject of several news reports charging that the pollution emitted by its factory endangers the health of hundreds of residents in a subdivision. The corporation filed an action in federal court against the residents to obtain a declaratory judgment that it complied with environmental regulations and is not responsible for any subsequent harm. A federal statute authorizes this suit.

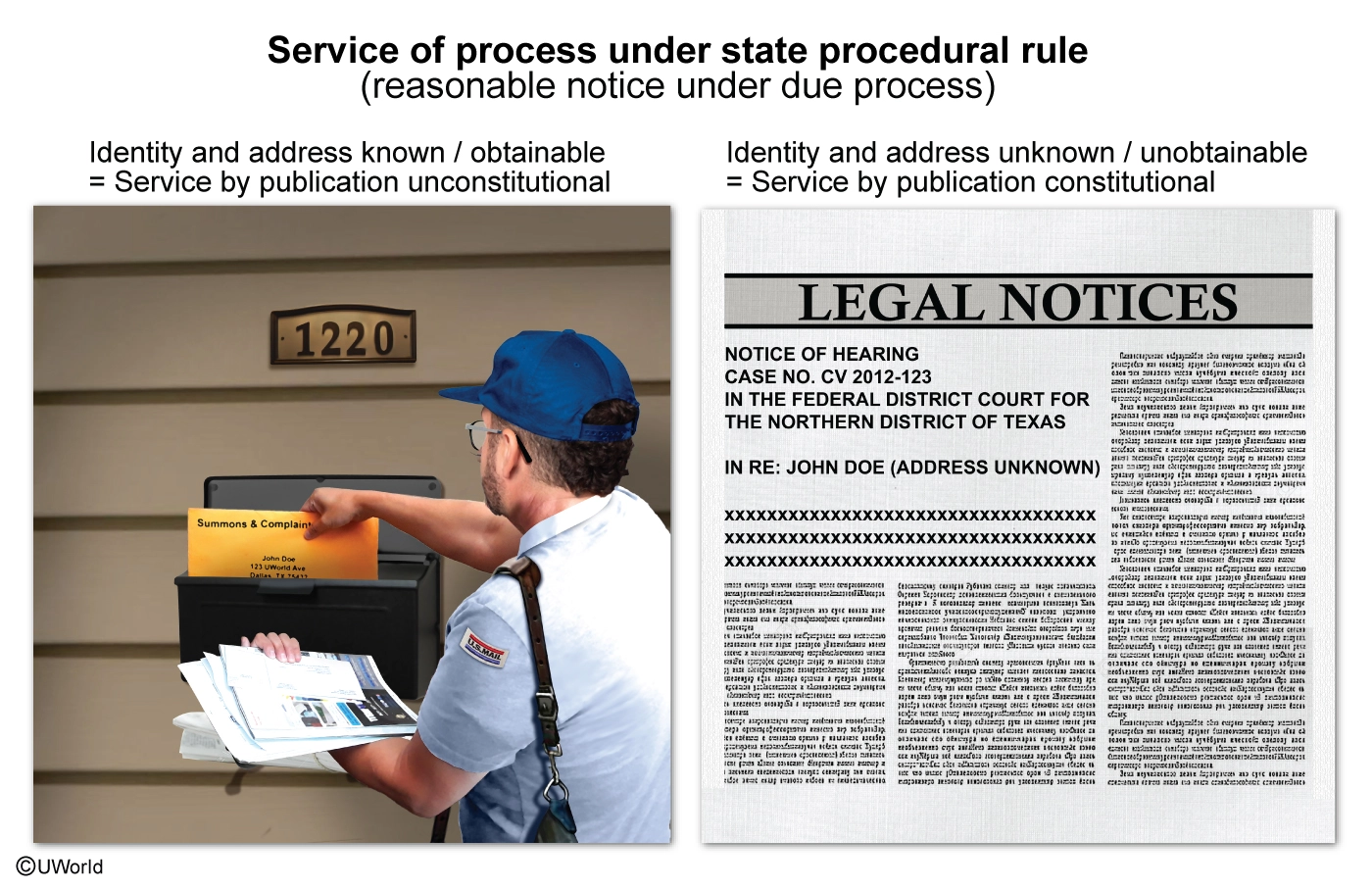

The state in which the federal court is located permits service of process by mail or by publishing notice of the suit in a newspaper. The corporation obtained the name and address of each resident in the subdivision from the county tax assessor. To avoid the expense of mailing service to each resident individually, the corporation published notice of the suit in the subdivision's community newspaper pursuant to the state's procedural rules.

Did the corporation properly serve the residents with process?

| A. | No, because service by publication was unreasonable since the corporation knew the name and address of each resident. | |

| B. | No, because the residents were not personally served with process. | |

| C. | Yes, because service by publication was reasonable due to the expense associated with mailing service to each resident. | |

| D. | Yes, because the newspaper publication provided the residents with reasonable notice of the action. |

A plaintiff must provide the defendant with adequate notice of a lawsuit through service of process, which must comply with both procedural rules and due process. In a federal court action, Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 4 permits service of process on a defendant-individual located in the U.S. by any of the following methods:

- Personal service – when process is delivered in person to the defendant

- Substituted service – when process is delivered to the defendant's agent or left at the defendant's dwelling with a resident of suitable age and discretion

- State procedural rules – when process is served pursuant to the rules of the state where the court sits or service is attempted (as seen with the newspaper publication here) (Choice B)

However, attempted service must also satisfy due process. Under this constitutional requirement, service must reasonably apprise the defendant of the pending suit so that the defendant may appear and present objections. This means that the plaintiff must notify the defendant of the lawsuit by the most reasonable means under the circumstances.

Service by publication is the most reasonable means in the rare instance when the defendant's identity or address is unknown and unobtainable. But if the plaintiff knows or can reasonably obtain this information, a more reasonable means of service must be used (eg, service by mail). Here, the corporation had obtained the residents' names and addresses from the county tax assessor, so service by publication was unreasonable. Therefore, the residents were not properly served with process (Choices C & D).

Educational objective:

A plaintiff must provide the defendant with adequate notice of a lawsuit that reasonably apprises the defendant of the suit so that the defendant may appear and present objections. Service by publication is permitted only when the defendant's identity or address is unknown and unobtainable.

References:

- Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(e) (service of process on individual in the United States).

- Mullane v. Cent. Hanover Bank & Trust Co., 339 U.S. 306, 319 (1950) (holding that a plaintiff cannot provide notice by publication when the identities and addresses of the defendants are known or easily ascertainable).

- 62B Am. Jur. 2d Process § 206 (2020) (explaining service by publication).

Arriving at the correct answer is important, but understanding why it’s correct is just as critical. At UWorld Legal, we go beyond simple answer keys by providing detailed explanations for correct and incorrect options. This approach helps reinforce your understanding and sharpens your ability to analyze similar questions from different angles.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the 7 Civil Procedure topics covered on the MBE?

The 7 civil procedure topics covered on the MBE are:

- Jurisdiction and Venue

- Pretrial Procedures

- Motions

- Law Applied by Federal Courts

- Jury Trials

- Verdicts and Judgments

- Appealability and Review

What is the difference between specific and general jurisdiction?

For a court to assert authority over a defendant, it must establish that the defendant has sufficient contacts with the forum state. This can be demonstrated through general jurisdiction, which allows a court to hear any case involving the defendant if they have continuous and systematic connections to the state. Alternatively, specific jurisdiction applies when the legal dispute arises directly from the defendant’s activities within the state, such as where the defendant resides or where the conduct in question occurred.16

What are the 2 types of jurisdiction in federal courts?

Federal courts have 2 forms of subject-matter jurisdiction: diversity jurisdiction and federal-question jurisdiction. Diversity jurisdiction applies when the case involves parties from different states and meets the monetary threshold. Federal-question jurisdiction applies when the dispute arises under the U.S. Constitution, federal law, or a treaty.17

What are the basic requirements of diversity jurisdiction?

To establish diversity jurisdiction, the case must meet 2 conditions. The amount in controversy must exceed $75,000, and there must be complete diversity, meaning no plaintiff can reside in the same state as any defendant.18

What is the complete diversity rule?

What is supplemental jurisdiction?

Supplemental jurisdiction allows a federal court to hear additional claims that do not independently qualify for federal jurisdiction, as long as they stem from the same core dispute or event as the primary claim.19

What is the 2-step analysis to determine if supplemental jurisdiction applies?

To apply supplemental jurisdiction, 2 criteria must be met. The additional claim must arise from the same case or controversy as the original claim, and the court must already have valid jurisdiction over at least 1 of the claims involved.19

What are the most tested topics in MBE Civil Procedure?

The most frequently tested topics in Civil Procedure on the MBE include Jurisdiction and Venue, Pretrial Procedures, and Motions. Together, these 3 categories account for 66.6% of Civil Procedure questions, with approximately 5-6 questions on each. The remaining topics — Law Applied by Federal Courts, Jury Trials, Verdicts and Judgments, and Appealability and Review — make up 33.3% of the section, with 2-3 questions allocated to each.1

Read Other MBE Subjects

References

- National Conference of Bar Examiners. (2023). MBE subject matter outline. Retrieved from

https://www.ncbex.org/sites/default/files/2023-01/MBE_Subject_Matter_Outline.pdf - FindLaw. (n.d.). Federal vs. state courts: Key differences. Retrieved from

https://www.findlaw.com/litigation/legal-system/federal-vs-state-courts-key-differences.html - Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Diversity jurisdiction. Cornell Law School. Retrieved from

https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/diversity_jurisdiction - Constitution Annotated. (n.d.). Fourteenth Amendment—Section 1—Due process. Congress.gov. Retrieved from

https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/amdt14-S1-7-1-1/ALDE_00000907/ - Constitution Annotated. (n.d.). Article III—Section 2—Clause 1—Case or controversy requirements. Congress.gov. Retrieved from

https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/artIII-S2-C1-16-7/ALDE_00013247/ - American Bar Association. (n.d.). How courts work: Cases—pretrial. Retrieved from

https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_education/resources/law_related_education_network/how_courts_work/cases_pretrial/ - Justia. (n.d.). Pre-trial and post-trial motions. Retrieved from

https://www.justia.com/trials-litigation/lawsuits-and-the-court-process/pre-trial-and-post-trial-motions/ - CaseFleet. (n.d.). How to file and write a motion to dismiss. Retrieved from

https://www.casefleet.com/blog/how-to-file-and-write-a-motion-to-dismiss - Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Rule 4: Summons. Cornell Law School. Retrieved from

https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frcp/rule_4 - Constitution Annotated. (n.d.). The Seventh Amendment—Right to a jury trial. Congress.gov. Retrieved from

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CONAN-2022/pdf/GPO-CONAN-2022-21.pdf - Texas Courts. (n.d.). Jury service in Texas. Retrieved from

https://www.txcourts.gov/about-texas-courts/juror-information/jury-service-in-texas/ - Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Collateral estoppel. Cornell Law School. Retrieved from

https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/collateral_estoppel - State Bar of California. (n.d.). Notice to 2025 bar exam takers. Retrieved from

https://www.calbar.ca.gov/Admissions/Examinations/California-Bar-Examination/Notice-to-2025-Bar-Exam-Takers#:~:text=Approved%20that%20beginning%20with%20the,person%20at%20vendor%2Drun%20or - Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Supplemental jurisdiction. Cornell Law School. Retrieved from

https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/supplemental_jurisdiction - Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. (n.d.). 2020–2021 updates to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Retrieved from

https://www.federalrulesofcivilprocedure.org/2020-2021-updates-to-the-federal-rules-of-civil-procedure/ - Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Specific jurisdiction. Cornell Law School. Retrieved from

https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/specific_jurisdiction - Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Federal-question jurisdiction. Cornell Law School. Retrieved from

https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/federal_question_jurisdiction - Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Diversity jurisdiction. Cornell Law School. Retrieved from

https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/diversity_jurisdiction - Constitution Annotated. (n.d.). Article III—Section 2—Clause 1—Judicial power. Congress.gov. Retrieved from

https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/artIII-S2-C1-11-6/ALDE_00013331/