The Judiciary of Vermont adopted the Uniform Bar Examination (UBE®) in July 2016. The UBE is a standardized bar examination comprising the Multistate Bar Examination (MBE®), the Multistate Essay Examination (MEE®), and the Multistate Performance Test (MPT®).

Vermont has announced it will replace the UBE with the NextGen bar exam beginning July 2027.

Vermont Bar Exam Structure

The Vermont Bar Exam spans the last Tuesday and Wednesday of February and July, with about 6 hours of testing daily.

| Vermont 2026 Bar Exam Structure | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tuesday | Wednesday | ||

| Morning (3-hour session) |

2 MPTs | 100 MBE multiple-choice questions | |

| Afternoon (3-hour session) |

6 essay questions, including the IQL |

100 MBE multiple-choice questions | |

Vermont Bar Exam Subjects and Topics

The Vermont Bar Exam evaluates your understanding of foundational legal principles, practical lawyering skills, and federal law through the following 3 components.

MPT

The MPT assesses your ability to carry out practical legal tasks in a simulated environment. You’ll complete 2 90-minute tasks set in a fictional jurisdiction known as “Franklin,” which operates under its own legal framework distinct from U.S. and Vermont laws.

Each task provides comprehensive documents, including relevant and irrelevant information. Success requires critical thinking and a solid grasp of essential legal principles.

| MPT Abilities Tested | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sort through the detailed factual materials | Separate relevant/irrelevant facts | ||

| Analyze statutes, cases, and administrative materials | Identify and resolve ethical dilemmas | ||

| Communicate effectively in writing | Complete a lawyering task within time constraints | ||

Learn More

MEE

The MEE consists of 6 essay questions. Each question involves 1 or more of the subjects listed below. Some subjects may be paired together, and others could be omitted. While it's impossible to know which subjects the National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE®) will choose for any given exam version, some have been tested more frequently than others historically.

For example, Civil Procedure has appeared on nearly every MEE in the past decade, while Criminal Law has only appeared

| MEE Subjects | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Business Associations | Evidence | ||

| Civil Procedure | Family Law | ||

| Conflicts of Law | Real Property | ||

| Constitutional Law | Secured Transactions | ||

| Contracts | Torts | ||

| Criminal Law & Procedure | Trusts & Estates | ||

Learn More

MBE

The MBE assesses your ability to apply fundamental legal principles and reasoning to fact patterns across 7 areas of law. Of the 200 multiple-choice questions, only 175 are scored, while 25 serve as unscored field tests for future exams.

| MBE Subjects | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Civil Procedure | Constitutional Law | ||

| Contracts | Criminal Law and Procedure | ||

| Evidence | Real Property | ||

| Torts | |||

Learn More

UWorld MBE Sample Questions

Quality speaks for itself. Try some of our free MBE sample questions below.

A husband and wife were married in State A and lived there for 10 years before separating. One month later, the wife permanently moved to State B and immediately filed for divorce in a federal court in State B. The wife claims that she is entitled to $300,000 in alimony. The husband appeared in the action and has filed a motion to dismiss for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction.

Should the court grant the motion?

- No, because the court has diversity jurisdiction over the case.

- No, because the husband waived a subject-matter jurisdiction challenge by appearing in the case.

- Yes, because state courts have exclusive jurisdiction over this type of action.

- Yes, because the wife did not establish a domicile in State B.

Explanation:

| Federal diversity jurisdiction exceptions |

|

Federal courts cannot exercise diversity jurisdiction over cases involving:

|

A federal court must possess subject-matter jurisdiction to hear the merits of a case before it. Subject-matter jurisdiction can be established through either:

- federal-question jurisdiction – when a claim arises under the U.S. Constitution, a treaty, or federal law (not seen here) or

- diversity jurisdiction – when the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000 and the opposing parties are citizens of different states.

Here, diversity jurisdiction is established since the wife claims that she is entitled to $300,000 and the parties are citizens of different states (States A and B). However, federal courts cannot exercise diversity jurisdiction over cases involving probate matters or domestic relations. Instead, state courts have exclusive jurisdiction over these types of actions (Choice A).* Therefore, the husband's motion to dismiss should be granted.

(Choice B) A challenge to subject-matter jurisdiction is never waived. However, a challenge to personal jurisdiction is waived if the defendant has voluntarily appeared in the case, unless it was a special appearance for the express purpose of objecting to personal jurisdiction.

(Choice D) An individual is a citizen of the state where he/she is domiciled—ie, physically present with the intent to remain indefinitely. Since the wife permanently moved to State B, she has established her domicile there.

Educational objective:

Federal courts cannot exercise diversity

jurisdiction over cases involving probate matters or domestic relations. Instead, state courts

have exclusive jurisdiction over these types of cases.

Bluebook Citations :

- Ankenbrandt v. Richards, 504 U.S. 689, 703–04 (1992) (explaining the domestic-relations exception to diversity jurisdiction).

A congressional committee investigated the pharmaceutical industry and found that the high cost of prescription drugs purchased and sold in the United States negatively impacted the nation's economy and the health of its citizens. In response, Congress passed a statute that regulates "the retail prices of every purchase or sale of prescription drugs in the United States."

A group of pharmaceutical companies challenged the constitutionality of this statute in federal court.

What is the strongest argument in support of the constitutionality of this statute?

- Congress may enact statutes for the general welfare.

- Congress may regulate the prices of all domestic purchases and sales of goods.

- The Constitution grants Congress the power to regulate the interstate transportation of prescription drugs.

- The purchases and sales of prescription drugs in the United States substantially impact interstate commerce in the aggregate.

Explanation:

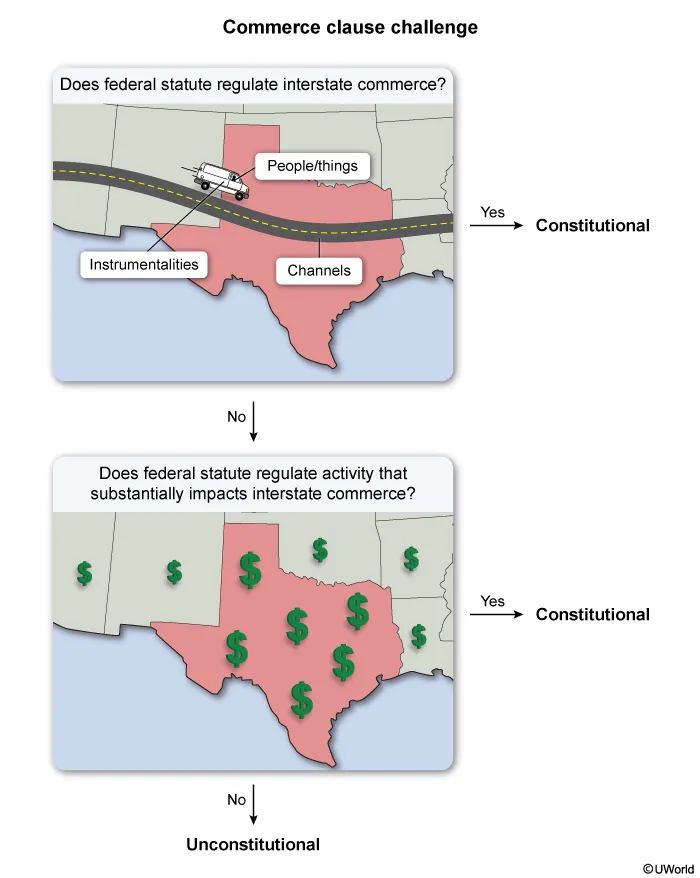

The commerce clause gives Congress broad power to regulate interstate and foreign commerce. This includes:

- the channels of interstate and foreign commerce (eg, roadways)

- the instrumentalities of interstate and foreign commerce (eg, vehicles)

- persons and things moving in interstate or foreign commerce (eg, goods and services) and

- in-state activities that, singly or in the aggregate, substantially impact interstate or foreign commerce.

Since Congress's commerce power is broad, federal statutes are constitutional if there is any rational basis for concluding that the regulated activity substantially affects interstate or foreign commerce. This can be shown through express congressional findings.

Here, the federal statute regulates the retail prices of prescription drugs in the United States. Congress has the authority to regulate such products' interstate transportation, but this statute also regulates in-state purchases and sales (Choice C). Since the congressional committee found that the high cost of prescription drugs negatively impacted the nation's economy, it is rational to conclude that their aggregated in-state purchases and sales substantially impact interstate commerce. Therefore, this is the strongest argument to support this statute.

(Choice A) The taxing and spending clause empowers Congress to tax and spend for the general welfare. But regulating prices is not equivalent to taxing or spending.

(Choice B) Congress cannot regulate the prices of every domestic purchase and sale of goods since it cannot regulate purely in-state sales that do not substantially affect interstate commerce.

Educational objective:

The commerce clause empowers Congress to regulate (1)

channels and instrumentalities of, (2) persons and things moving in, and (3) in-state activities

that—singly or in the aggregate—substantially affect interstate or foreign commerce.

Bluebook Citations :

- Gonzales v. Raich, 545 U.S. 1, 17 (2005) (explaining Congress's broad authority under the commerce clause).

The owner of a new office building contracted with a well-known landscaper to design and install landscaping around the building for $30,000. The agreement was memorialized in writing, was signed by both parties, and called for a budget of $5,000 for trees, shrubs, sod, and materials. The contract required the landscaper to complete the work within six months. Due to an unexpected increase in the price of trees and shrubs, the landscaper abandoned the project and never completed any of the work.

Three years after the landscaper's deadline, the building owner sued the landscaper for breach of contract. In the jurisdiction, the statute of limitations for breach of a services contract is two years after the breach, and the statute of limitations for breach of a sale-of-goods contract is four years.

Can the owner recover damages from the landscaper?

- No, because the contract is divisible with respect to the services and goods, and the landscaper's breach is therefore subject to the two-year statute of limitations.

- No, because the contract primarily calls for services, and the landscaper's breach is therefore subject to the two-year statute of limitations.

- Yes, because the landscaper's breach was a result of an increase in the price of goods, and his breach is therefore subject to the four-year statute of limitations.

- Yes, because the landscaper's breach was willful, and he is therefore estopped from denying that his breach is subject to the four-year statute of limitations.

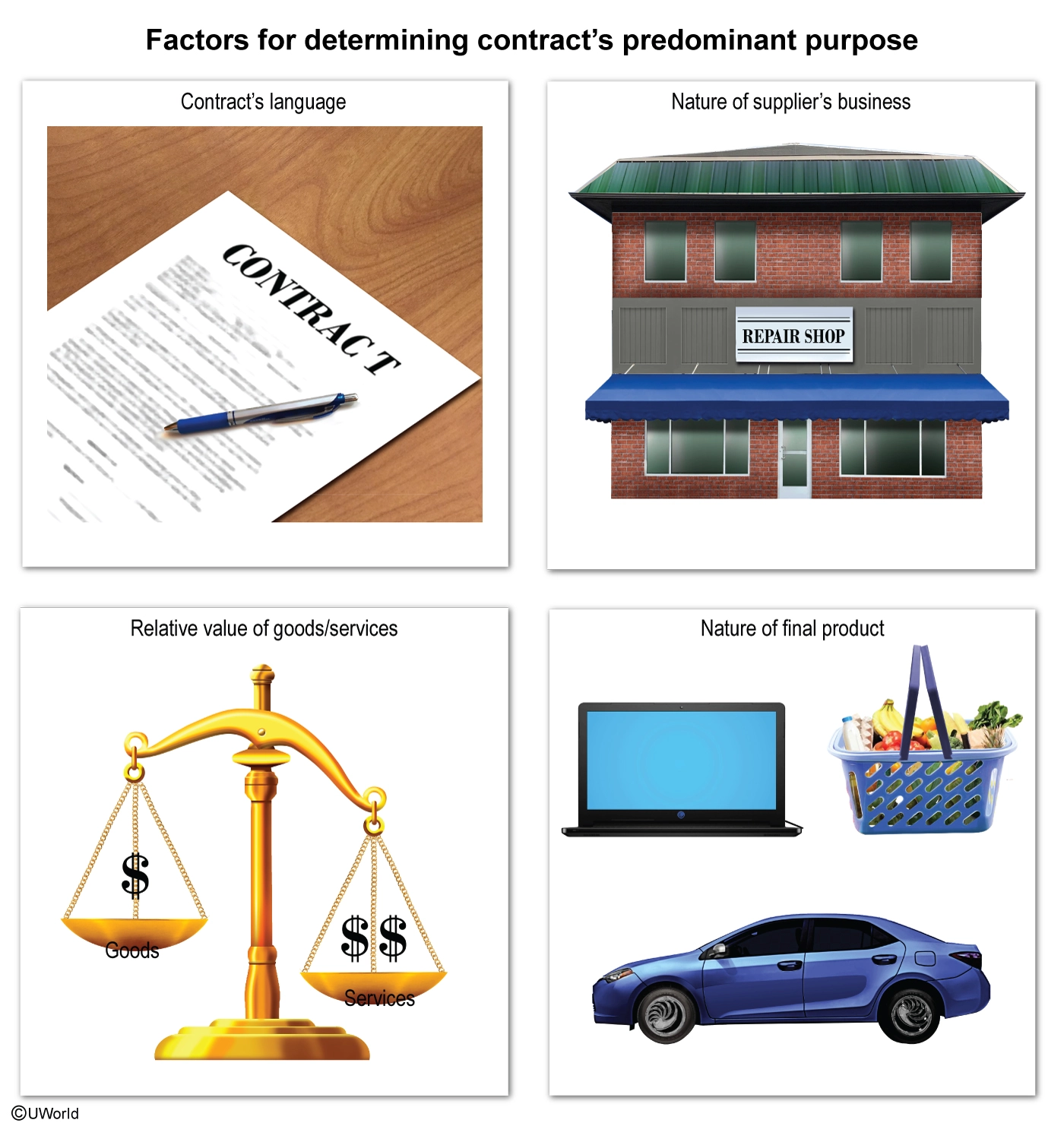

Contracts for the sale of goods are governed by Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), while contracts for services are governed by common law. However, some contracts involve the sale of goods and the rendering of services. To determine which law applies to a "mixed" or "hybrid" contract, courts ask whether its predominant purpose was the sale of goods or the rendering of services. The following factors are relevant to this determination:

- The contract's language

- The nature of the supplier's business (ie, whether it typically provides goods or services)

- The relative value of the goods and services

- The nature of the final product (ie, whether it can be described as a good or service)

Here, the building owner contracted to buy goods (eg, trees, shrubs, sod) and services (ie, designing and installing the landscaping). The owner likely hired the well-known landscaper due to his skill in performing landscaping services, and the $5,000 budget for goods was just one-sixth of the $30,000 contract price. Therefore, the contract primarily calls for services and is subject to the jurisdiction's two-year statute of limitations. And since the owner sued three years after the breach, the owner cannot recover damages from the landscaper.

(Choice A) The predominant-purpose test is unnecessary when a contract is divisible—ie, when the payment for goods can easily be separated from the payment for services. But here, the contract is likely indivisible since it combined the sale of the trees, shrubs, and sod with their installation.

(Choices C & D) The predominant-purpose test focuses on the parties' reason for entering the contract—not for breaching it. Therefore, it is irrelevant that the landscaper's breach was (1) a result of an increase in the price of goods or (2) willful.

Educational objective:

Sale-of-goods contracts are governed by the UCC,

while services contracts are governed by common law. When a contract calls for the sale of goods

AND the rendering of services, the contract's primary purpose determines whether the UCC or

common law applies.

Bluebook Citations :

- Bonebrake v. Cox, 499 F.2d 951, 960 (8th Cir. 1974) (applying the predominant-purpose test to determine which statute of limitations applies to a mixed contract for goods and services).

- Princess Cruises, Inc. v. Gen. Elec. Co., 143 F.3d 828, 833 (4th Cir. 1998) (listing factors that courts consider when applying the predominant-purpose test).

A man and a woman dated for several weeks. During that time, the man repeatedly asked the woman to have sex. Each time, the woman responded that she would not have sex with the man unless they were married. One evening, the man promised the woman that they would elope the following weekend if she would agree to have sex. The woman agreed and the couple had sex. The following weekend, the man told the woman that he had no intention of eloping and only made that promise to get the woman's consent. The woman reported the man to the police, who later arrested and charged the man with rape.

Is the man guilty of rape?

- No, because fraud in factum did not negate the woman's consent.

- No, because fraud in the inducement did not negate the woman's consent.

- Yes, because the woman's consent was obtained by fraud in factum.

- Yes, because the woman's consent was obtained by fraud in the inducement.

Explanation:

| Consent to sexual intercourse obtained by fraud | ||

| Type of fraud | Definition | Effect |

| In factum |

|

Negates victim's consent |

| In inducement |

|

Does not negate victim's consent |

In most modern jurisdictions, rape is defined as sexual intercourse with another without that person's consent.* This means that rape did not occur if the victim consented to sexual intercourse. However, a victim's consent may be ineffective if it was obtained by fraud. There are two types of fraud:

- Fraud in factum – when consent is obtained by fraud regarding the nature of the act itself, leaving the victim unaware that he/she consented to sexual intercourse and negating the victim's consent

- Fraud in the inducement – when consent is obtained by fraud regarding what the victim knows is an act of sexual intercourse, which does not negate the victim's consent

As a result, consent obtained by fraud in factum is not a valid defense to rape, but consent obtained by fraud in the inducement is a valid defense.

Here, the man falsely promised the woman that they would elope if she agreed to have sex with him. Since the woman knew that the act to which she consented was sexual intercourse, her consent was obtained by fraud in the inducement (Choices A & C). This type of fraud did not negate the woman's consent, so the man is not guilty of rape (Choice D).

Educational objective:

Fraud in factum occurs when the fraud pertains to the nature of the act itself and negates a rape victim's consent. In contrast, fraud in the inducement occurs when fraud is used to gain consent to what the victim knows is an act of sexual intercourse and does not negate the victim's consent.

A plaintiff sued a defendant for negligence to recover damages that the plaintiff suffered as a result of a crash between the two parties. At trial, the plaintiff's attorney called the plaintiff's wife to testify as to what she witnessed on the day of the crash. On cross-examination of the wife, the defendant's lawyer elicited several responses that tended to show that the plaintiff's actions constituted contributory negligence. The plaintiff's attorney seeks to ask the wife several questions on redirect examination, but the defendant's attorney objected.

What is the strongest argument that the court must allow redirect examination of the wife?

- The plaintiff's attorney failed to provide all significant information on direct examination.

- The plaintiff's attorney seeks to reiterate the necessary elements of the claim.

- The plaintiff's attorney seeks to reply to all matters raised on cross-examination.

- The plaintiff's attorney seeks to reply to significant new matters raised on cross-examination.

Explanation:

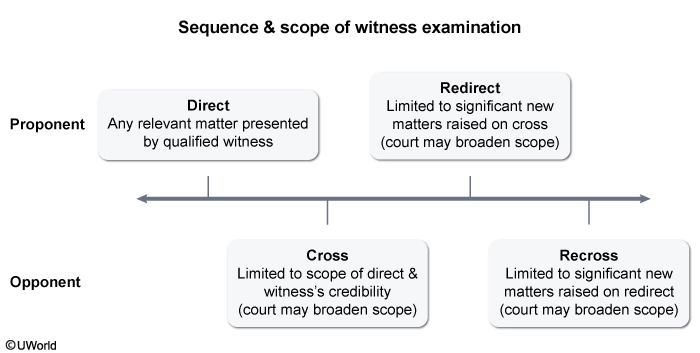

Federal Rule of Evidence 611 gives trial courts the authority to exercise reasonable control over the mode and order of examining witnesses at trial. This includes the discretion to determine whether—and to what extent—redirect examination of witnesses should be permitted. But when a party raises a significant new matter while cross-examining a witness, the court must allow the opposing party to address that matter through redirect examination.

Therefore, the strongest argument for allowing redirect examination of the plaintiff's wife is that the plaintiff's attorney seeks to reply to significant new matters that were raised on cross-examination.

(Choice A) A party is expected to elicit all significant information during direct examination of a witness. Therefore, a court need not permit redirect examination to allow the party to provide information inadvertently omitted on direct examination.

(Choices B & C) Redirect examination is generally limited to significant new matters raised on cross-examination. Therefore, a party is not entitled to redirect examination to (1) reiterate information like the necessary elements of the claim or (2) reply to all matters addressed in cross-examination.

Educational objective:

When a party raises a significant new matter on cross-examination of a witness, the court must allow redirect examination by the opposing party to address that matter.

Bluebook Citations :

- Fed. R. Evid. 611 (explaining the mode and order of examining witnesses).

Twenty years ago, a man who owned a 20-acre ranch agreed to sell all of his mineral rights to his neighbor. The man executed a warranty deed conveying the mineral estate to the neighbor, who failed to record the deed.

The following year, a woman moved her mobile home onto an undeveloped five-acre portion of the man's ranch. After the woman had lived on the property for 10 years, a local drilling company began operations on a nearby tract to drill a natural gas well. Believing that the woman owned the property, the drilling company approached the woman about leasing the mineral rights on her property and requested that the woman sign a lease of her mineral rights. The woman signed the lease as requested, and it was promptly and properly recorded. The drilling operations were successful, and the drilling company prepared to distribute profits from royalties. However, a dispute arose between the neighbor and the woman, as both parties claim ownership of the minerals.

The period of time to acquire title by adverse possession in the jurisdiction is 10 years.

In an action to determine title, is the court likely to award title to the mineral estate to the woman?

- No, because the woman actually possessed only the surface estate that had previously been severed from the mineral estate.

- No, because the woman did not actually possess the mineral estate until she signed the lease of the mineral rights.

- Yes, because the neighbor failed to record the warranty deed conveying the mineral estate.

- Yes, because the woman adversely possessed both the surface estate and the mineral estate for the statutory period.

Explanation:

An adverse possessor can acquire title to land owned by another if his/her possession of the land is:

- Open and notorious – apparent or visible to a reasonable owner

- Continuous – uninterrupted for the statutory period

- Exclusive – not shared with the owner

- Actual – physical presence on the land and

- Nonpermissive – hostile and adverse to the owner.

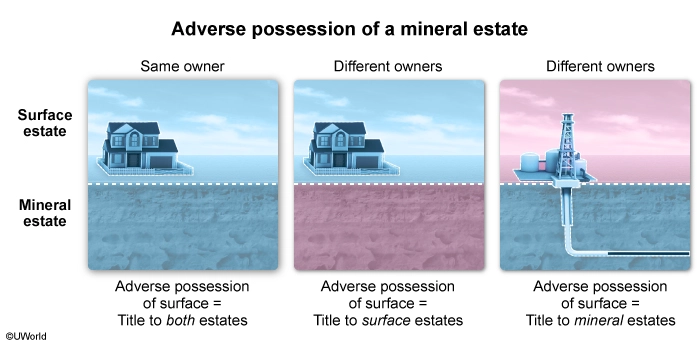

If the surface and mineral estates are owned by the same party, then the adverse possessor will acquire title to both estates—even if only one estate is actually possessed. But if the mineral estate has been severed from the surface estate (ie, the surface and mineral estates are owned by different parties), then the adverse possessor will only acquire title to the estate that is actually possessed. The mineral estate is actually possessed when the adverse possessor mines or drills wells on the land.

Here, the neighbor purchased the mineral estate from the man, thereby severing the mineral estate from the surface estate. And since the woman merely lived on the property for the 10-year statutory period—she did not attempt to mine or drill a well on the mineral estate—she actually possessed only the surface estate during that time (Choice D). This means that the woman did not adversely possess the mineral estate, and the court is not likely to award her title to that estate.

(Choice B) Adverse possession of a mineral estate requires the commencement of drilling or mining operations. Merely signing a lease of the mineral rights is not enough.

(Choice C) A deed need not be recorded to be valid, so the neighbor's failure to record has no impact on whether the woman adversely possessed the mineral estate.

Educational objective:

If a mineral estate has previously been severed from the surface estate (ie, surface and minerals owned by different persons), then an adverse possessor can only acquire title to the mineral estate by actually possessing the minerals (eg, by mining or drilling wells).

A teenager was riding a bicycle when she saw a classmate walking toward her. The teenager rode quickly toward the classmate, knowing that he would think she would run into him on her current trajectory. The teenager was not purposefully trying to harm or touch him. The classmate saw the teenager riding toward him and yelled at her to stop. The teenager swerved at the last moment and avoided hitting him. The classmate had a panic attack because he thought that the teenager would hit him.

Is the classmate likely to succeed if he sues the teenager for assault?

- No, because the teenager did not make contact with the classmate.

- No, because the teenager did not purposefully try to harm or touch the classmate.

- Yes, because the teenager acted with the requisite intent.

- Yes, because the teenager's conduct was extreme and outrageous.

Explanation:

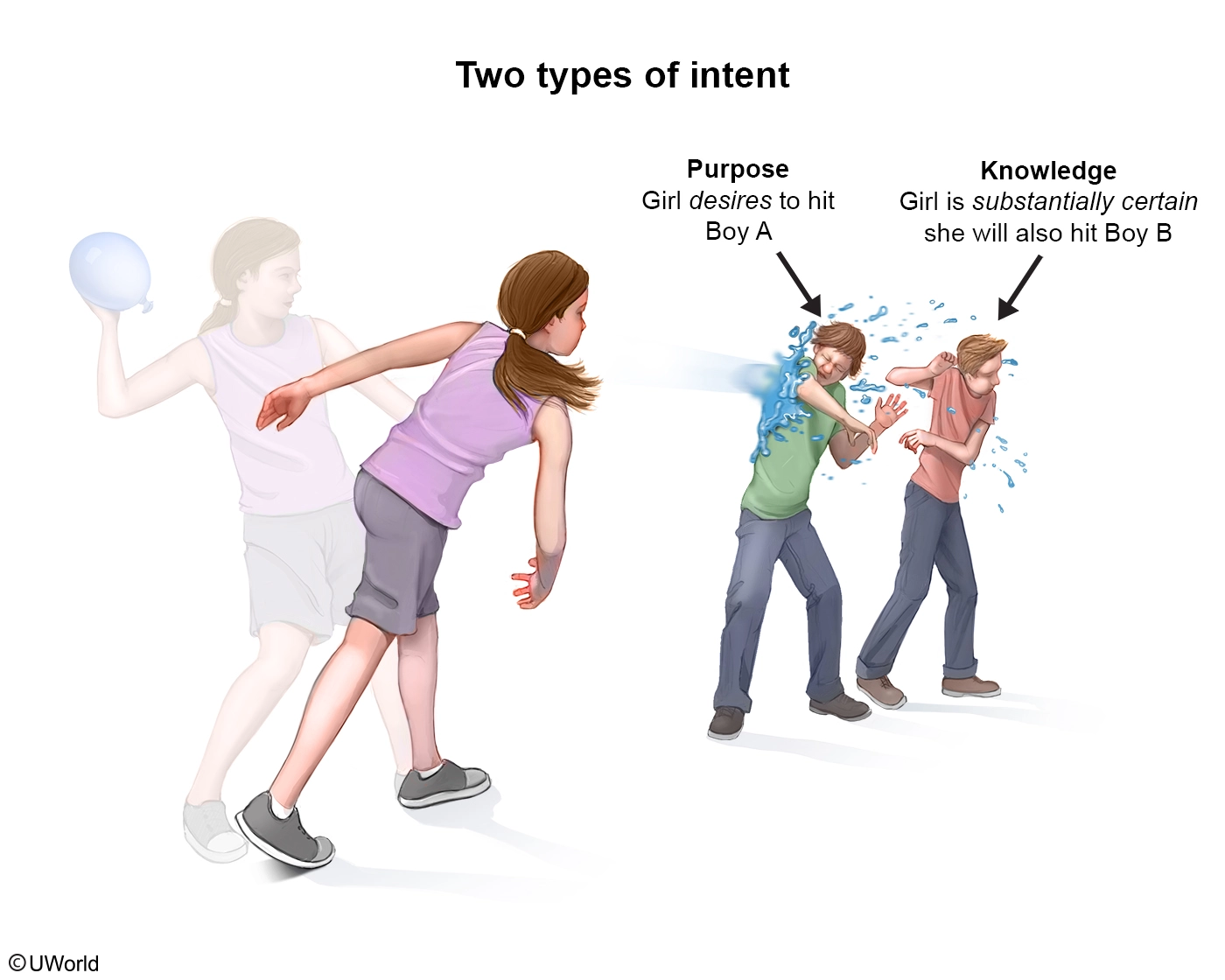

Assault occurs when (1) a defendant intends to cause the plaintiff to anticipate an imminent, and harmful or offensive, contact with the plaintiff's person and (2) the defendant's affirmative conduct causes the plaintiff to anticipate such contact. The intent requirement is met when the defendant acts with either:

- purpose – the desire to cause anticipation of an imminent harmful or offensive contact or

- knowledge – the substantial certainty that the plaintiff will suffer such anticipation.

Here, the teenager rode her bicycle directly at her classmate, causing him to think that she would hit him (anticipation of imminent contact). And since the teenager knew with substantial certainty that the classmate would think she would run into him, she acted with the requisite intent. As a result, the classmate is likely to succeed in a suit against the teenager for assault.

(Choice A) Assault merely requires that the plaintiff be placed in anticipation of imminent contact. Actual bodily contact is not required. Therefore, the fact that the teenager did not make contact with the classmate is irrelevant.

(Choice B) The intent to make contact with the plaintiff is a requirement for battery, but assault merely requires the intent to cause the plaintiff to anticipate imminent contact. Therefore, the fact that the teenager did not purposefully try to harm or touch the classmate does not absolve her of liability for assault.

(Choice D) Extreme and outrageous conduct (i.e., conduct that is unacceptable in civilized society) is an element of intentional infliction of emotional distress—not assault, which only requires intentional conduct.

Educational objective:

For assault, intent exists when a defendant acts with the purpose (desire) or knowledge (substantial certainty) that his/her conduct will cause the plaintiff to anticipate an imminent, and harmful or offensive, contact.

- Restatement (Third) of Torts: Intentional Torts to Persons § 105 (Am. L. Inst., Tentative Draft No. 1, 2015) (providing the elements for assault).

Take a look at a typical competitor sample question. Their practice questions might parody the exam, but ours consistently meet or exceed exam-level difficulty. Their limited explanations address the correct answer choice but do not go the extra mile to explain the incorrect choices, so you don’t make the same mistakes on exam day.

A mother gave her land to her 2 kids, a son and a daughter, as joint tenants. The son built 2 adjoining homes on the land. He lived in 1 house and rented the other. The daughter lived out of the country and never visited the land. The daughter needed money, so she sold her interest in the land to her ex-boyfriend. Her ex-boyfriend immediately hired a developer to build a 3rd home on the land. Soon after the daughter had sold her interest in the land, she was killed in a motorcycle accident. The ex-boyfriend is now asking the court for a judicial partition of the land. The son contends that upon his sister’s death, he was now the sole owner of the land.

How should the court rule?

- For the ex-boyfriend, because he plans to live on the land.

- For the ex-boyfriend, because he paid for the son’s interest in the land.

- For the son, because he has the right of survivorship.

- For the son, because he has the sole position of the land.

Explanation:

Correct answer: B

Vermont Bar Exam Requirements

To sit for the Vermont Bar Exam, you must meet specific educational and certification requirements depending on whether you’re a law school student, foreign-educated lawyer, or seeking admission without examination.

Law School Students

You must take the Vermont Bar Exam within 5 years of graduating from an American Bar Association (ABA)-accredited law school or completing the Law Office Study Program. To apply for the early examination, you must submit a transcript proving that you will have completed 5 semesters of law school (including academic instruction on each subject tested on the UBE) before taking the UBE.

Non-approved U.S. Law Schools

Graduates from non-ABA-accredited U.S. law schools can apply for the Vermont Bar Exam if the school was seeking accreditation during their attendance and hasn't been denied it since. Vermont also allows bar admission through the Law Office Study Program (LOS Program), requiring 25 weekly study hours with a lawyer or judge over 4 years. You must hold a bachelor's degree from a U.S. Department of Education-accredited institution or foreign equivalent and submit the required registration, certification, and completion forms.

Foreigner Lawyers and Students

If you graduated from a foreign law school not accredited by the ABA, you may petition to take the Vermont Bar Exam by demonstrating good cause. To qualify, you must have passed the bar examination in another state and be a member in good standing of that state’s bar.

Admission on Motion (Reciprocity)

To apply for admission to the Vermont Bar without examination (Admission on Motion), attorneys must have practiced law for 5 of the last 10 years. The 5-year requirement can be waived if:

- Practicing law for 6+ months in a jurisdiction requiring more than 5 years of admission for motion applicants.

- Practiced law in Maine or New Hampshire for over 3 years before applying (special reciprocity with Vermont).

Vermont does not have legal education requirements for Admission on Motion, but applicants must:

- Not have failed the VT Bar Exam or scored below 270 on the UBE in the past 5 years.

- Have passed the UBE within 3 years (5 years if practicing law for 2+ years).

- Have passed the Multistate Professional Responsibility Examination (MPRE®) within 3 years before, or 1 year after, the application.

- Complete at least 15 hours of certified Continuing Legal Education (CLE).

- Participate in a mentorship program in Vermont's first year of practice.

- Establish good moral character and fitness.

| Address | Vermont Board of Bar Examiners Costello Courthouse 32 Cherry St., Suite 213 Burlington, VT 05401 |

Scheduling

To sit for the Vermont Bar Exam, follow these steps:

- Create an NCBE account and complete the Standard Character and Fitness Electronic Application.

- Submit the Vermont and NCBE applications together via Odyssey File and Serve.

- Arrange for your law school to send a Dean’s Certificate of Study to the Board.

- Submit a letter from your law school confirming academic instruction on all UBE subjects and preparedness for the exam (required for early examination).

- Provide a recent photo taken within the last 6 months.

- Submit fingerprint cards with fully rolled fingerprints.

- Submit special accommodations and laptop testing forms, if applicable.

- Review the Application with Examination Checklist to ensure all steps are completed.

Vermont Bar Exam Deadlines, Fees, and Cost-Saving Options

Submit your Vermont Bar Exam application early to give yourself time to gather all necessary documents and avoid late fees. See key deadlines, fees, and payment options below.

Exam Dates and Deadlines

| Filing Deadline | February 2026 | July 2026 |

|---|---|---|

| Timely Deadline | Nov. 15, 2025 | April 15, 2026 |

Fees

| Vermont Bar Exam Fees | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vermont Bar Exam | $300 | ||

| Late filing fee | $50 | ||

| Application for admission without examination | $800 | ||

| UBE score transfer | $525 | ||

| Non-approval law school equivalency determination | $50 | ||

| First-time registration of Law Office Study | $200 | ||

| Fee for filing of each 6-month report | $100 | ||

| Administration fee for any application | $50 | ||

| Character and fitness report | Schedule | ||

Payment Policies

Application fees are non-refundable, even if your application is denied.

Cost-saving Options

Scholarships and grants are available to help Vermont law students and graduates with legal education and bar exam costs.

- Explore scholarships and grants offered by Vermont Law & Graduate School based on merit, needs, and opportunity.

- Check out the AccessLex Institute Law School Scholarship Databank for additional scholarship options.

- Visit the ABA website for 100+ programs and opportunities for law students and young lawyers.

Vermont Bar Exam Bar Exam Scoring and Grading

Vermont’s minimum passing score is 270. Since the UBE is divided into 2 equally weighted sections — writing (MPT/MEE) and the MBE — you want to aim for a 135 on each section. However, you do not need to score 135 on each section to pass.

For example, an exceptional score on the MBE can balance out a subpar score on the writing section. What's important is that the sum of your 2 scores is 270 or higher.

Component Weights:

- MBE: 50%

- MEE: 30%

- MPT: 20%

Vermont Bar Exam Results and Pass Rates

As is common with bar exams nationwide, the Vermont Bar Exam’s pass rate for repeaters is considerably lower than for those taking it for the first time. This is likely because many repeat takers don’t modify their study habits.

| Exam | Overall Pass Rate | First-Timer Pass Rate | Repeater Pass Rate | Results Release Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| July 2025 | TBA | |||

| February 2025 | 31% | 40% | 9% | April 7 |

| Exam | First-Timers | Repeaters | Overall | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | No. of Candidates | Pass Rate | No. of Candidates | Pass Rate | No. of Candidates | Pass Rate |

| 2024 | 55 | 58% | 18 | 39% | 73 | 53% |

| 2023 | 72 | 67% | 20 | 40% | 92 | 54% |

| 2022 | 81 | 59% | 30 | 20% | 111 | 49% |

| 2021 | 138 | 62% | 34 | 26% | 172 | 55% |

| 2020 | 139 | 75% | 17 | 18% | 156 | 69% |

| 2019 | 100 | 62% | 17 | 47% | 117 | 60% |

| 2018 | 98 | 77% | 19 | 26% | 117 | 68% |

| 2017 | 80 | 69% | 31 | 32% | 111 | 59% |

Additional Vermont Bar Requirements

To become licensed and maintain your license in Vermont, you must pass the MPRE and meet the Character and Fitness requirements.

MPRE Requirements

The MPRE is a 2-hour, 60-question multiple-choice exam assessing knowledge of professional conduct. You must pass with a score of 80 or higher. Registration is available through the NCBE.

Learn More

Character and Fitness Requirements

In Vermont, the NCBE handles the character and fitness review after you pass the bar exam. This review must be approved before you can join the state bar. It assesses your integrity, judgment, and responsibility based on your disclosed personal, academic, and professional history and requires complete transparency for approval.

Vermont Board of Bar Examiners Contact Information

See the details below to contact the Vermont Board of Bar Examiners with inquiries regarding the Vermont Bar Exam.

| Medium | Info |

|---|---|

| Phone Number | (802) 859-3000 |

| Fax | (802) 859-3003 |

| Andrew Strauss, Licensing Counsel [email protected] |

|

| Mailing Address | Office of Attorney Licensing Costello Courthouse 32 Cherry St., Suite 213 Burlington, VT 05401 |